Whatever God you believe in, you are going to say “Oh” when you listen to this hex that puts you to sleep.

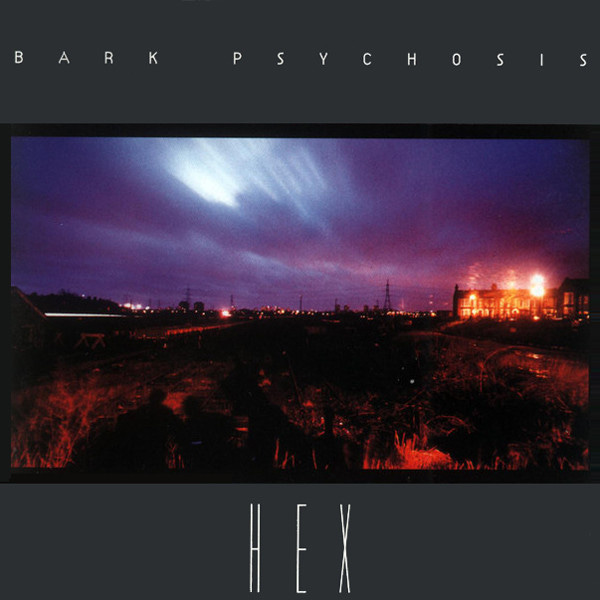

I’m talking about Bark Psychosis’ only album released in 1994, Hex, which is only 7 tracks (6, actually) that will simulate the feeling of waiting in line at the DMV for 50 minutes.

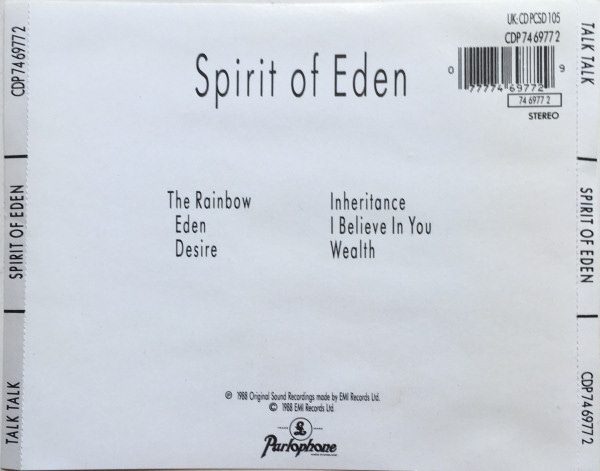

I admit, there is something perverted about the post-Mark Hollis fan club. Ever since Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock, bandmates Paul Webb and Lee Harris thought they too could make something experimental and original like what happened in Eden. Many of the troupes and techniques that Hollis laid out in those albums were up for grabs, and of course, some young kid was bound to mimic and emulate what Hollis did during his obsession with creating an anti-music simulacrum of Jazz fusion meeting John Cage.

Around this same time, Graham Sutton’s noise band, “Bark Psychosis,” had nothing to contribute to the sea of other punk bands. So why not plagiarize all the techniques Hollis wrote about and call it something of Sutton’s own “genius?”

Throughout the entire press coverage and legacy of the lone debut album, it had nothing to offer outside of itself. Hex broke up the band, leaving Sutton to become friends with Lee Harris. They both get drunk, and through strange judgment, let Sutton contribute to the new formation of “.O. Rang” that same year. They want me to think of him as a natural replacement for Hollis. Call it, “Bark Bark.”

Sutton in 2017 spoke at the Waterstones book store at Selborne Walk in London. He said,

“I was really into them [Talk Talk] in 1984, and when I was 12, for some really weird reason I was connected to them. …[every new album is] a strange new world. I could listen to them over and over and hear different things every time. …The band was befriended by a man named John Ward, …who was impersonating the drummer from Talk Talk, Lee Harris. …I contacted the [Talk Talk] manager… give a note to the real Lee! …We met up. He introduced me to Phill Brown… We ended up working on things together… But yeah, Talk Talk, love them.”1

Also, he notes his interest in Brown in a written interview,

"Scum' was as close as they would veer into late Talk Talk territory, at least in terms of their working methods. This may well be why they ended up working with Spirit Of Eden and Laughing Stock engineer Phill Brown, who offered technical advice for the complicated recording process and also mixed the results.”2

Now that both Lee Harris and Phill Brown are on his side, that makes him the defacto Hollis expert!

So why do I have to bring this up? There are many cases in which Sutton feels like a super fan of Mark Hollis and believes every action of his has to relate to what Hollis does.

Sutton wrote something peculiar about his musical upbringing,

“One of my earliest memories was being three or four and being completely obsessed with 'The Infernal Dance' from Stravinsky's The Firebird Suite," he recalls. "I would play it at massive volume, with my head on the speaker, and just feel thrilled, terrified and overwhelmed. I'd get such a rush from it. I ended up having a long phase of nightmares about it, to the point where my parents binned it!”3

Yes. He likes the same type of classical that Hollis likes too. It could be about Franco Donatoni, Maurice Ravel, or Béla Bartók. Stravinsky feels safe enough to not sound like a Hollis ripoff.

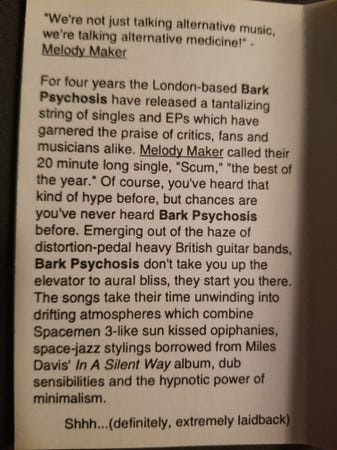

But alas, it reminds me of something similar that was written on the promo cassette release of Hex:

…“In a Silent Way,” …really?? Mark Hollis wrote about his love for Miles Davis too! This feels way too awkward, in a strange way.

According to Sutton,

“It seemed like a natural and exciting decision to utilize the massive space above us. I loved the sound of old Miles Davis records, and I wanted to capture the solidly 3D feeling of sound waves moving through air, creating something holographic, rather than through some processing, which always seemed to lack that true immersiveness."

Yikes. It’s going back to Mark Hollis when he said that the John Coltrane record “In a Sentimental Mood,” “sounds like the bloke’s setting his kit up.”4

And then this should sound familiar as well,

“For some reason, I just flipped one day and I realized silence could have a much greater impact than loud noise... Space and silence are the most important tools you can use in music. I just got really obsessed with that."5

Silence!? It sounds exactly like the same classical music and silence obsession of Hollis, right? Why would Sutton copy word-for-word what Hollis likes and call it his unique genius to make an album nobody has ever heard of? The 2020 documentary about Mark Hollis is even called “In a Silent Way” and highlights how Hollis loved silence as an artistic device!

So why do all the mainstream outlets love talking about Hex and promoting it as some amazing album you should listen to before you die, you might ask? Well, there was a Chud-looking guy named Simon Reynolds, who listened to the album once and concluded it was “post-rock” music or something to do with “post-modernity,” or whatever. Given Reynolds close connection with Mark Fisher and their interest in the reference fallacy that is “invoking cultural memory,” of course, they will all say that Hex sounds like some “beautiful” or “elegant” personal expression of “intimacy,” when that’s just high-end rhetoric to disguise the noisy nothing burger that has some lullaby loops here and there. The album from the start was from a noise band that had nothing to offer, and ends with common sense that the entire album is just plain dreadful to listen to.

In context, Reynolds wrote,

“The future of rock is looking more buoyant than it has for a while, thanks to Bark Psychosis and their 'post-rock' ilk.”6

I understand some one-hit wonder albums do make it, like Slint’s Spiderland or Aqua’s Aquarium, but these are very rare cases of success. Hex comes off as a lame excuse from a man competing with other English noise bands at a time when alternative and shoegaze were becoming popular. You already had My Bloody Valentine’s 1991 album, Loveless, and in that same year of 1994, Starflyer 59 also released their debut album. Hex is another example of an album that was influenced by the climate of experimentation and personality in the early 1990s. So instead of going with the flow of distorted guitars, it was more akin to Dead Can Dance messing with samplers and synths trying to create an “environment” of “feelings.” Oh jeez.

Hex even tried to copy the album back of Spirit of Eden. Just look at the compare-and-contrast back cover tracklistings together.

It becomes so apparent that every track seems to lift off another Talk Talk riff.

“The Loom” has the same stupid shakers found in “The Rainbow.” It also has that same vibe of “Happiness is Easy,” or the same sad piano in “Once Upon Your Lips” by Dance House Children. It reeks of the annoying “ShoZygs” or broken Variophon sound you might hear in “After The Flood.” It feels way too kitsch.

Sutton, in the same review of Reynolds’ post-rock declaration, said that,

“Noise is important. I could never understand people I knew who liked Talk Talk and saw it as something 'nice to chill out to' when I loved the overwhelming intensity and the dynamics.”7

This type of emotional fight, between “noise” and “silence” is a gag with Hex. The recurring gag is that every 3 minutes, on the same track, the song drastically changes into some frustrating and predictable loop. It’s like they stopped making a song at the 4-minute mark, and decided to dub over another electronic track on it. You kill two birds with one stone.

Sutton has a pretentious technique. "We only had a couple of reels of tape, so we'd just keep playing, recording 'til the reel ran out, listening and erasing before we had something we liked." It’s not the same ending magic that happened on “Ascension Day,” that’s for sure. Instead, you get more jams without substance.

“A Street Scene” is like a poppy “After The Flood” with its crashing chorus. The same type of Tim Friese-Greene melodica is heard in “Absent Friend,” exactly like in “I Believe In You.” And why not have an obnoxious harpy synth playing for an extra two minutes? It’s like Earthworm Jim Special Edition for Windows 95 which isn’t working correctly and is lagging in execution (“but that’s what makes it cool!”).

“Big Shot” feels like “John Cope” without the input. Even the whole gag of “The Rainbow” shakers or the “After The Flood” moodiness is still there. The vibraphone has to go. It immediately ruins the vibe. I don’t care if this was recorded in the dark or in a big church to get all sentimental. The vibraphone fucking sucks.

Journalist Wyndham Wallace writes,

“Illuminated only by the dim glow of their equipment and the strip lights in the corridor beyond, they work in near darkness, at times transported from their grim surroundings by the sheer intensity and euphoria of what they're creating. The confined space they occupy – with amplifiers in each of its four corners, and drums lining the wall - magnifies the already exaggerated dynamics of the noise they're creating, so much that the walls seem to be moving in and out.”8

Yes, both Talk Talk and Bark Psychosis recorded their music in a church. The reverb, split mixing, and the “play what you want” haunts the creative process. Three years later in 1991, everyone wanted a slice of pie that was Laughing Stock, and nobody got it right.

Wallace continues,

“Like two of its inspirations, Spirit Of Eden and Laughing Stock, Hex paid no mind to the possibilities (or otherwise) of performing its songs live: this was indeed the sound of the studio used as an instrument in itself – the "fictional acoustic space" of which Reynolds had written – enabling grand gestures and minute details alike to add texture to the music's substance.”

Yes, it’s about “texture” for these people. How shallow.

“Fingerspit” is an obvious rip of “Taphead.” The dynamics of loud and soft are annoying, and not innovative. The piano interlude goes back to “The Rainbow” and the surf guitar doesn’t add up. Hollis did a better job on Anja Garbarek’s “The Gown” than Fingerspit trying to emulate the chorus break. I don’t care if Lee Harris contributed to the drum section!

Sutton thought about it,

“At its crudest, it was a sort of 'reel them in, then bludgeon them' strategy. Then the seduction would begin again. The whole quiet-loud thing has now become another cliché, but for a while it felt viscerally exciting to us, and was something that felt very natural. It was all tension and release, I guess, with a view towards some kind of transformative sensual experience: for us, and, hopefully, for any people that had turned up to some toilet of a pub to watch us play."

A perfect example of this “quite-loud” thing is Fingerspit. It has to be the most kitsch track on this album. It’s nothing like “Chameleon Day” or “Taphead.” This track is so off in so many ways.

“Eyes and Smiles” tries to be “New Grass” without anything original. And because he couldn’t get Mark Feltham on harmonica, there is some interesting emulation in the center, but otherwise, forgettable. “Pendulum Man” is the worst track on the album. It doesn’t even try. Even if Christoph de Babalon or Brian Eno made this track, it would still be considered a “good” filler with no substance. But for the case of Bark Psychosis, it’s forgettable. At this point, you have to stop the CD player and leave. There is nothing the listener is missing. That’s why this album is actually 6 tracks and not actually 7. Don’t count this one. I think to myself that Talk Talk’s noisy b-sides of “Stump” and “5:09” do better justice than any track on Hex. Even “It's Getting Late In The Evening,” a jammy b-side, does better justice than “Big Shot.”

Bark Psychosis has to be the most broken and out-of-tune band passed as avant-garde “good music” I ever heard. It’s exactly like The Shaggs; so bad, you have to at least admire the experimentation. You can’t listen to Bark Psychosis. You can only “feel” what Sutton is trying to project, along with Reynolds who’s also telling you that the miracle water is also magical.

Listening to Bark Psychosis live is also a horrendous act. Merzbow has something to jam to when he is deliberately performing noise. Unfortunately, Bark Psychosis can only “play” things and call it “rock music.” Their performance at ICA in London on May 5th, 1994 is perhaps the worst thing I’ve ever listened to. No defense of “No Wave” could ever justify this abomination of boredom.

Bark Psychosis is a perfect example of a band that has been propagated by liberal media as “innovative,” “groundbreaking,” or even “pioneering” that no one can use common sense that the music is shit. How could Hex ever be pioneering when it is, in fact, a 14-year-old attempt and misunderstanding of what Mark Hollis was doing? When you make bad music, you save face by fooling people that this is “new” or a special kind of music beyond what anyone is doing at the moment. Give the noise some expensive lawyer and tell it has something to do with postmodernity, and everyone understands it a decade later. If music is just about “emotion and heart,” you won’t find it in Hex.

Sutton remarks,

"The whole thing about being in this band is never repeating yourself. I've always tried to surprise myself and other people as well, fucking around with people's preconceptions about what you're about and stuff. I really get a real huge fucking kick about giving people the wrong impression. Or twisting things around. Like, it might sound initially sweet, but it ain't. Or vice versa.”9

No way would I ever allow Sutton to bully me to get his perversion and misreading of Hollis over me! He even has no shame trying to act like him too!

And back to Wallace,

“Hex is a record whose comforting melancholy is best enjoyed in a single sitting, much like those which inspired it. But to say it's ripe for rediscovery is inaccurate: in a sense, it's never gone away. It's simply bided its time, keeping a low profile, allowing people to find it at the same, composed pace at which the record gestated and, indeed, operates.”

I have tried to appreciate this album by giving it a few multiple relistens. I just don’t get it. Whoever is behind such a dastardly public relations campaign can only say that “A Street Scene,” “Absent Friend” or “Big Shot” is worth radio play, but doesn’t stick at the end and become incredibly forgettable tracks. The faulty argument relies on the assumption the sounds of the hollow synth or the surf guitar make you feel like you are lost in a bad vintage computer game. This ultimate shallowness is what’s happening to music right now. It doesn’t save the integrity of music but destroys it with a shallow intellectualism that only cares about superficial understandings and fashion. What is “beautiful” can’t be compared to 500 years of music in the making.

This is a bad album only worth the memories of someone stuck in 1994 and never leaving it.

Wallace concludes,

“…it's more because Bark Psychosis' intentions were simply to put rock behind them. Everything that followed was intuitive. Intuitive and startling.”

There was nothing special about Bark Psychosis. Ever.

I give it 1 out of 5 stars.

-pe

10-27-2023

Post Rock_Fearless_Moonshake and Bark Psychosis in conversation with Jeanette Leech October 30th, 2017.

(https://youtu.be/CPrB819eDLE?si=EWYftxedtb-zUyBt)

Wallace, Wyndham (August 14, 2014). “I Put A Spell On You: The Story Of Bark Psychosis & Hex.” The Quietus. (https://thequietus.com/articles/15990-bark-psychosis-hex-graham-sutton-interview)

Ibid., [2].

“Mark Hollis Talks About Laughing Stock” - Promo Cassette Interview (1991)

"Interview with Graham Sutton (taken by US zine Audrie's Diary, 1994)". Audrie's Diary. Archived from the original on 24 April 2009.

Reynolds, Simon (March 1994). "Bark Psychosis: Hex". Mojo. No. 4. London.

Ibid., [6].

Ibid., [2].

Ibid., [5].