Against William Gibson

"Cyberpunk" as praise for Silicon Valley elitism and American imperalism

“I know what I'm up against... No rose without a thorn!... And the last thing I'll stand for is ideas to get the better of me! I know that rubbish from '18 ..., fraternity, equality, ..., freedom ..., beauty, and dignity! You gotta use the right bait to hook 'em. And then, you're right in the middle of a parley and they say: Hands up! You're disarmed..., you republican voting swine!—No, let 'em keep their good distance with their whole ideological kettle of fish ... I shoot with live ammunition! When I hear the word culture ..., I release the safety on my Browning!”

-Hanns Johst

Jack London’s The Iron Heel imagines a dystopian future where the Bay Area is in charge of the nation and its people. Just like today, the poor live on the street, as the rich romanticize about their conditions. A constant feedback loop happens where donating money towards the poor becomes mandatory, just so they can be sedated from revolution, all while the rich can still keep their yachts. Call it “woke capitalism.” This is a reflection on the state of San Francisco today and what is to come post-2020.

William Gibson is a pulp science-fiction writer who made an obvious and clever observation about the future, at the right time, in 1984. I enjoyed Burning Chrome, Neuromancer, Virtual Light, and Idoru as a teenager. But all of it was nothing profound. Nostradamus would predict similar future events, and either everyone would believe it, or disregard it.

Gibson, however, transpired Bay Area acceleration in his Bridge trilogy.

He predicts the following themes in his work.

1. The internet will rule us.

2. The Japanese will rule us.

3. Computers will be central to our behavior.

4. And as technology advances, “Lowlifes” and youth subcultures will exist within it.

Even Amazon is working on The Peripheral as a television series! The Gibson estate is loved by the Tim Cook class of CEOs who want this dystopia to be a utopia.

Now did any of these things come true as of 2021?

The Bridge trilogy sounds like a love letter to those who work in San Francisco. STEM degrees and an interest in programming are preferable. In close hindsight, Gibson already has been debunked about technology, subcultures, late capitalism, and the decline of the Japanese nation. But why is Gibson, a stooge for the information age, celebrated by our elite as the Grand Poobah of internet culture? Both white Gen-Xers and Millennials seem to dig this romantic subculture of “cyberpunk” as a coming-to-age, rite of passage.

Has nobody ever criticized that Neuromancer is not as playful as we imagine? In other words, “Cyberpunk” did not create a hybrid subculture that would resist authority, but instead, gave power to the Californian tech-savvy culture that continues to oppress us. Don’t bother resisting cyberpunk, just “stay in the pods, eat the bugs, and don’t have kids.”

There is nothing “punk” about cyberpunk.

Was it just a pulp genre to renovate a dying pulp industry? Maybe the bourgeois would become literate again if Issac Asimov was mixed with Hubert Selby Jr.? Is this the truth? As Norman Spinrad would say, to paraphrase, “New Romantics, or Neu-ro-man-tic?” Nothing more than an 80’s "fusion of the romantic impulse with science and technology.” The post-baby boomer generation saw an America with early electronic music, Japanese imports, and ditzy fashion. Would this lead to anime futurism?

But as critic Charles de Lint would argue, “It just goes to show you that while research will always be an indispensable tool, imagination remains the most vital component of good storytelling. Imagining story, the inner workings of his characters' minds, and the world in which it all takes place are all more important than research in the long run."1

If “imagination” supersedes research, this might explain the depravity of the “Narratology vs. Ludology” game design schools, the “performative” over the “programmer” in electronic music, and other lazy arguments against analytical work. Normal “storytelling” is insidious because of how it takes every disciplined art form down to egalitarian ideology. Gibson believes that a writer who has any interest in any “hard science” is an actual fascist.

Exactly, what is romantic about “lowlife” behavior? Has technology shaped humanity into “Homo Americanus?” As de Lint puts it, that Neuromancer, “inspired countless men and women who were computer savvy to try to bring his vision to life.”

How many repressed computer programmers wanted to be cool punk rock n’ roll stars? They desired this role, at the expense of imagining a future where both anime-futurism and dirty ghettoism are abundant.

Is this a good thing?

We should consider William Gibson as a con artist working with the Silicon Valley elite. His love for Japanese society is dated and irrational. The values of cyberpunk do not benefit electronic musicians or intellects alike. A celebrity being dubbed as a “pioneer” leads to suspicion. Gibson is praised as a spokesman, not as an intellect. A poster child for subcultural distraction.

On Technology

Jacques Ellul wrote about the impact of technology on society through academic commentary. His writing is often regurgitated by both Luddites and transhumanists alike. A theme in Ellul’s work is that technology often enslaves us, and we never have the power to regulate it. Controversial intellects like Timothy Morton argue that we must respect “object-oriented ontology,” and that “nonhuman” objects have souls! While I agree with Ellul, I believe Gibson would side with Morton, on the issue that objects dictate the will of humanity.

For example, the popular K-Drama Replay 1988 is a nostalgic trip to Korea in the late 1980s. The drama is one of the highest-rating shows in Korean cable television history. But what made the show successful was not about its melancholy story, but rather, the nostalgia wrapped up around commercial products, aesthetics, and technology of 1988. The drama focuses on the objects that cater to a group of teenagers. Obsolete traditions, like writing in a “diary,” filming with a VHS camera, and looking up stores in a phone book, all have an impact on Korean society. This is even more interesting, as it contradicts the premise of Neuromancer that Japanese society rules the 1980s. However, the neglected and shunned controversial state of Korea is just as powerful and culturally significant as Japan in 1988. Replay 1988 was released in 2015, three decades after the cyberpunk fad, and yet gives us insight into a culture and aesthetic Americans were ignorant of. Gibson arrogantly claims that “Japan was already ‘cyberpunk’ before my writing,” but I am very doubtful that the Japanese read Neuromancer or found a single, liberal American man powerful enough to create the Heisei period. Neuromancer was written at the end of the Shōwa period, a “fascist” and violent period, which many Japanese secretly hold dear to themselves. The Japanese government still ignores talking about issues like Korean “comfort women” and its imperial intentions to rule China. Korean, on the other hand, is presented as the innocent bystander as Gibson enjoys the accelerating capitalism of Japan.

To prove Gibson’s obsession with object-oriented ontology, Gibson wrote Neuromancer on a 1927 olive-green Hermes portable typewriter. Ironic, considering he is writing about the future of obsolete technology. Neuromancer celebrates the fact that subcultures will arise with overabundant technology, that we rely exclusively on computers, “icebreakers,” cybernetic upgrades, and abstract, non-scientific virtual reality spaces implemented by MMORPGs. He also advocates the arrogant cuckoldry that Japan will be the globalized power celebrating the death of white America’s regime. All of this is nothing more than sorrow expressed by the white bourgeoisie, who survived the middle-class suburbia project of the 1950s. Gibson might believe this American monoculture is “problematic.”

Even more embarrassing, since 1984, Gibson has only managed to write 12 novels, some popular tech articles, and a whole lot of self-promotion about himself. Hell, even a documentary film celebrating Gibson was released in 2000. With only one celebrated book attached to his name, how long must this endless press praise go on? Are we ever allowed to deconstruct this golden calf?

I recall first discovering his work back in 2009 at The Bookateria Two in Ocean City, New Jersey. The book I found was Count Zero, and it made absolutely no sense. It came off as a pretentious cyber cowboy novel with a forgettable plot. When I googled searched his name, I found his Wikipedia article. Almost a decade ago, the Wikipedia article glorified him as it is today. The wiki page is nothing more than a public resume to trick big bankers and tech oligarchs into hiring Gibson at whatever shows they may have. Something tells me that Gibson is a huckster who makes money by advocating a Silicon Valley society where we are all glued to our smartphones, imagining a peaceful, egalitarian society through “cyberspace.” Gibson is not a programmer, nor a scientist, and yet he is celebrated for his sole “envisioning.” The problem is that Gibson is openly celebrating lowlife subcultures and digital cuckoldry. These are not signs of freedom, but traits of decay.

Ellul, a much more significant writer and intellect, is downplayed in favor of a spokesman for the information age. What Gibson is preaching is nothing new. And he continues to create this uninspiring art that rules over us.

On The Japanese

I enjoy Gibson’s fascination with Japanese society and the dream of anime-futurism. I do despise cuckoldry, and the self-hatred liberals have of themselves. Instead of fighting for a new identity politics, they insist any non-white people can secure their racial interest at the expense of a white, egalitarian one. Again, Gibson would be in utter shock to realize that the Japanese have been in decline for the last few decades, and an entire race cannot be defined simply by the hentai and video games they produce. Gibson admits Neuromancer as being dated, from the internet being nothing more than a collection of “silly stuff,” to his lost belief that it was a mysterious and sexy place.

He sees Japan as a technologically savvy society, a recurring theme in his work.2

In the '80s, when I became known for a species of science fiction that journalists called cyberpunk, Japan was already, somehow, the de facto spiritual home of that influence, that particular flavor of popular culture. It was not that there was a cyberpunk movement in Japan or a native literature akin to cyberpunk, but that modern Japan simply was cyberpunk. And the Japanese themselves knew it and delighted in it.

…Is it any wonder, then, that we continue to feel that the future somehow resides in Japan? But we have it backward, really: Japan lives in the future; it has lived there for a century. Hot-wired by repeated onslaughts of technologically driven change, temporally dislocated, deeply traditional yet subject to permutation without notice, we all, today, must to some extent feel ourselves to be warped, alien, disfigured.

The Japanese have simply had a head start.

Perhaps Gibson has never read Jared Taylor’s Shadows of the Rising Sun: A Critical View of the Japanese Miracle. In this study, Taylor debunks Western interest in the emerging Japanese society. He argues that the Japanese are still racially aware of the cosmopolitan world. They could never accept the assimilation of foreigners into their country. Because of this, Japanese growth in the 1980s was a fad, and Western interest in Japan was motivated by liberal intellects finding the “other” grand civilization. There is nothing special about the Japanese people. It is the bias and mysticism Westerners developed around them. Edward Seidensticker, Donald Keene, and Jack Seward praised the book for its daring study against popular culture fetishism.

In addition, the internet populism of Trump hurt Gibson’s wish for internet liberation. Even he became worried about Trump’s behavior, further frustrating North Korea, as he wrote this urgent letter to a New Yorker journalist.3

“But then Trump started fucking with N Korea, here, so how scary can my scenario be? He keeps topping me, but I think I can handle it in rewrite. And if there’s a nuclear war, at least I won’t have to turn in the manuscript!”

With this quote alone, my issue has always been that Gibson is biased towards the Korean people. If given a face-to-face discussion, he would never side with the Chinese or Koreans, who practically dominate world culture, but instead, he doubles down and sides with the poor Japanese he remembers in the 1970s.

Why? Because they make good art, and that he is a biased weeb.

Clearly, Gibson cannot be described as an Asian Studies professor. His fascination with the Japanese is a dated one, almost stereotypical one, relating to the post-WWII apology following the celebration of Japanese popular culture. Japan’s Heisei era was a gamble on the fact that Neuromancer was predicting the true endgame. As of 2010, Japanese birthrates continue to decline, while Korea rises in cultural power and threatens any Japanese dominance.

Sure, there is good popular Japanese music. I love Japanese bands like Shonen Knife, Cibo Matto, and Puffy. But Gibson believed there would be some Western hair metal orientalism fusion added to that aspect. More on the lines of Sigue Sigue Sputnik or X-Japan. There would be Eurasians in his future, just all half-Japanese or at least virtual holograms of the Japanese. It’s like keeping whiteness but with the unavoidable aspect that capitalism leads to a dystopian hell, where redemption is in the virtual worlds we become comfortable with.

…Just like TikTok? A platform operated by the Chinese government? Again, to Gibson’s disappointment, no romance can be found today in post-pandemic 2021.

On Hauntology

Technology always must bring about memories of the past. And the past is often what motivates us to go forward. A forgotten work by Gibson is his avant-garde, floppy disk poetry of Agrippa.4 The program can read the text file once, in a slow automation, before it distorts the page, and “eats itself” away. The reader would then be left with only the memory of the text. Much of what could be said, in the metaphorical sense in the poem, is about the transition towards adulthood, and a newfound appreciation of the childhood past. The past is a glimpse as we move towards the future.

Again, we are left with the insidious fad of “Hauntology,” which has reeked of modernity since the 1980s. Gibson is an advocate of modernity, and he sees only the philistine class going against it. Well, I see it nothing more as an enlightenment of Baby Boomer values. The dive into “postmodernity” is assuming modernity can be egalitarian, fair, and democratic, and seek social justice by new means. Memories that haunt us tell us to do politically motivated actions. This isn’t about the nostalgia and fun of the past, but how memories are “rhizomic” and chaotic without a start or an end. A hauntologic “good life” is one seeking social justice in an unjust world that negates nostalgia.

But why does technology evoke memory? And why is the literati so obsessed with praising nostalgia? Everyone has a “subjective memory” with no objective agreement. Is this a praise of radical individualism? In our fun-loving meme culture, subcultures are created by the products we like, pictures we share, and the likes and dislikes algorithm behind our favorite YouTube videos. Information is uploaded, and soon disappears over time, because of our incompetent servers and data archivists. Are we supposed to praise this unique behavior as something Wolf OS X argues for when comparing vaporware to Soundcloud streams without any backups? What’s the point of this unrecorded nostalgia?

In Gibson’s own words about Agrippa,

“Honest to God, these academics who think it's all some sort of big-time French philosophy—that's a scam. Those guys worship Jerry Lewis, they get our pop culture all wrong.”5

“Our” pop culture is wrong! Thank you very much!

This irony comes with Gibson’s love for Umberto Eco, the Italian esoteric academic, who is loved by many French intellects. Maybe Gibson’s exposure to “postmodernism” in his stint at university made him more pretentious and condescending towards the conservative pulp writers of the past.

On Science-Fiction

In Brian Aldiss’s Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction, Aldiss celebrates the young Gibson as being a forerunner in the future of science fiction writers. But science fiction in 2021, if it is a scene anymore, is not read by the public. I would argue that Gibson did not “renovate” science fiction, but ultimately put an end to it. The obsession with pre-PC computers, beatnik culture, and accelerating technology foresaw a future that oppresses us. Gibson doubted the legitimacy of any civilization moving forward.

Meanwhile, Gibson is an incredible proponent of Samuel R. Delany, the gay black writer who wrote the transgressive book, Hogg. I once had a professor who told me she didn’t like my “nazi shit,” but was enthralled by Delany’s Hogg. Hogg deals with themes of child molestation, incest, coprophilia, coprophagia, urolagnia, anal-oral contact, necrophilia, and rape. And then ask, why are anti-capitalist, race-realists bad? Hypocritical, yes? This “New Wave” of science fiction writers argued more for social change than actual “city-building tendencies.” Gibson’s writing becomes a cliche attempt to fuse Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, and Jack Kerouac into science fiction. The elite love to praise the class under them, and romanticize the struggles of being poor, all while distracting everyone with social justice politics.

Spin Magazine, in 1988, (only four years after Neuromancer) introduced his influence as a cool, “dangerous thing.”6 Read the following carefully.

In the last couple of years, science fiction has tossed off the little green men albatross and turned overnight into a sleek, well-oiled, dangerous thing—a matte-black Stealth bomber constructed of words. It has acquired all the sinuous grace and breathless, sweaty eroticism of the finest rock’n’roll; it kicks in with visceral urgency that smacks of addiction.

To a large degree, this is due to William Gibson, whose writings—Neuromancer, Count Zero, Burning Chrome, and the new Mona Lisa Overdrive—have taken the mainstream’s assumptions about science fiction (nerdy, reactionary, desexed) and rotated them 180 degrees on their vertical axis. Gibson’s stuff is the reactor-core steam of all tomorrow’s parties breathing down your neck today. He has smashed a hole through the moribund haze of the science fiction subculture like nothing since the New Wave of the late ’60s.

While the latter had long been a staple of bad science fiction, Gibson makes it breathe: When he writes about it, you can smell the heavy, fetid, urine-laden air and feel every drop of grime sputtering down from the sooty geodesic “sky.” Most of the mood of cyberpunk—the pacing, the language, the brand-name physicality—can be traced to his lead. His first short stories (the brilliantly incendiary troika “Johnny Mnemonic,” “New Rose Hotel,” and “Burning Chrome,” published in OMNI magazine at the dawn of the ’80s), wasted no time in establishing his trademark intensity as the standard by which all other future SF will be measured. It sent a shockwave through the science fiction community that brought similarly-minded writers crawling out of the woodwork, and nothing has been the same since.

If this is not social control, I’m not sure what is.

There is such thing as bad science fiction, and to Spin, it’s mostly all of it. If you like classic science fiction, you must be some kind of intellectual, fascist incel.

Gibson even compared Sex Pistol punk zines to science fiction, saying, “It fits right in with what I thought science fiction was supposed to be about.” Already, a dying genre of American pulp literature, Gibson thought he could make it cool for young people, assimilating punk culture with technology. The best example of this attitude comes from Helen Andrew’s commentary on Steve Jobs in her book Boomers: The Men and Women Who Promised Freedom and Delivered Disaster. Jobs, a hippy out of his parent’s garage, wins the influence of CEOs by advocating the “youth” subculture in his actions while selling out to the oligarch forces. Gibson, a fan of the dying science-fiction genre, becomes a stooge for the post Reaganomic new world order, by advocating a futuristic society unlike anything that was previously known to bourgeois white America. In essence, like his young self, Gibson has achieved success by delivering disaster to the rest of us.

On Fascism

As he proclaims to be an accurate science fiction writer, Gibson has shied away from any “hard science fiction,” and has stated fascism is within the canon.7

As he wrote in this interview.

“I took courses with a guy who talked about the aesthetic politics of fascism- we were reading an Orwell essay, "Raffles and Miss Blandish," and he wondered whether or not there were fascist novels- and I remember thinking, "Reading all these SF novels has given me a line on this topic- I know where this fascist literature is!" I thought about working on an M.A. on this topic, though I doubt that my approach would have been all that earthshaking. But it got me thinking seriously about what SF did, what it was, which traditions had shaped it, and which ones it had rejected.”

It becomes clear that Gibson ignores anything to do with the “cultural right,” and as a knee-jerk reaction to any movement against liberalism. As Maurice Bardèche would proclaim himself, “I am a fascist writer.” Has it not become evident that Gibson is ignoring, or plain ignorant, that writers like Bardèche have influenced other reactionary writers? But the irony is that Gibsons encourages everyone at the age of 21, to read Umberto Eco’s “Ur-Fascism.”8

If I were able to prescribe a single work as required reading, it would probably be Umberto Eco’s essay “Ur-Fascism,” bound as a pamphlet for pocket carry, and sympathetically translated into every language on earth.

Gibson, at least living now for 70 years, has never come to conclude that his favorite Japanese people also possess a “fascist” will of imperialism unto the world, or that the will of self-determination, for any race or people, is not a totalitarian nightmare as he claims it to be. For a man who moved to Canada to avoid the Vietnam draft, I’m not so sure if he became an obnoxious Canadian liberal, like Justin Trudeau, or envisions an educated society based upon American “freedom.” Gibson frantically enjoys the aspect that “every language on earth” can read about why fascism is evil, but can’t explain which groups and races prefer fascism as a moral good. After reading Ur-Fascism for myself, I can agree that those 14 points do describe a progressive, not regressive, radicalism against neoliberalism. Having such values does not make someone a “mean” or “genocidal” person, considering the very people who go against said values must mean “you are a bad person.”

Gibson must decry “fascism” as anti-freedom. But the irony is, the very people who are “anti-fascist,” brutally stop any “fascist” discourse “by any means necessary,” and are ok with censoring those who go against their adored liberalism and conforming modernism. Postmodernity does not question or resist modernity, instead, it embraces it. Modernity is not dead but has taken on wider definitions in a “post” era. My issue is with those who have an extreme obsession with liberalism. Liberalism is indeed a failed experiment. The white population, or the very people who advocated liberalism, continued to decline in birth rates. Meanwhile, they flood their own countries with non-whites as token “diversity” friends, all while securing their nice white gated communities for themselves. Vancouver, as of 2016, has a white population around 46%.9

Gibson is holding on to the last remnants of yuppy society.

On Eco

Much could also be said about Umberto Eco’s curiosity about fascism. His commentary from 1995 is outdated. Writing not as a devil’s advocate, but as a condescending liberal, Eco makes all the points a “shitlib” would write about on a Reddit page in 2021.

I have a list of 13 examples:

Umberto Eco is very sympathetic to Joseph, a black man from the USA. He shares his comics and black wisdom with Eco. Does the black man enrich the life of a white liberal? Do whites need “black music that black people don’t like anymore?” I feel that the same pathological altruism is within Gibson as well.

“The photographs of the holocaust,” is nothing but a technological error. What about those who questioned the legitimacy? Robert Faurrison? Paul Rassinier? Norman G. Finkelstein? This isn’t about denying the holocaust, it’s rather about the propaganda built upon advocating American liberalism. Gibson should know better, considering he is all about a “mega-corporate” conspiracy.

Anyone questioning this liberation is a part of the “communist lie” those evil “fascists” concocted to advocate irrational genocide. But the other slang, “liberation,” and of “different colors,” is a good thing.

“Nazi lite” must refer to those who believe in race realism and gender difference. Yet owning the means of production and advocating violence can only be for the liberated. If nazis do it, that’s evil.

“Is there another ghost haunting Europe?” Here we have the fad of hauntology.

“Nazism and Stalinism were true totalitarianism regimes.” Eco sounded like a true liberal here.

“Fascism in Italy has no special philosophy.” As Eco argues, “It was Hegelian!” I guess X can’t be Y, but Y can be X.

Gabriele D'Annunzio, according to Eco, “would be sent to the shooting range in Russia.” The importance of D’Annunzio is undeniable. He teaches us about sexuality and the meaninglessness of politics. Eco should know this too.

“Truth has been learned out for all.” Fascism believes in one narrative, and there can be no further advancement of learning. As if the individual rules out “truth” to be subjective learning? We all must grind in academia forever.

“Ur-fascism is defined as irrationalism.” Irrational? See above.

Eco misquotes Hanns Johst, and instead cites Hermann Göring for the quote, “When I hear the word culture, I reach for my gun.” Talk about being academically dishonest. Exactly, what is so evil about this quote alone? Dick Hebdige wrote about the implications of subculture in his book. Meanwhile, you have hippy proponents arguing, “When I hear the word gun, I reach for my culture.” Why is culture a good thing? According to Hebdige, and even René Girard, it can be a bad thing.

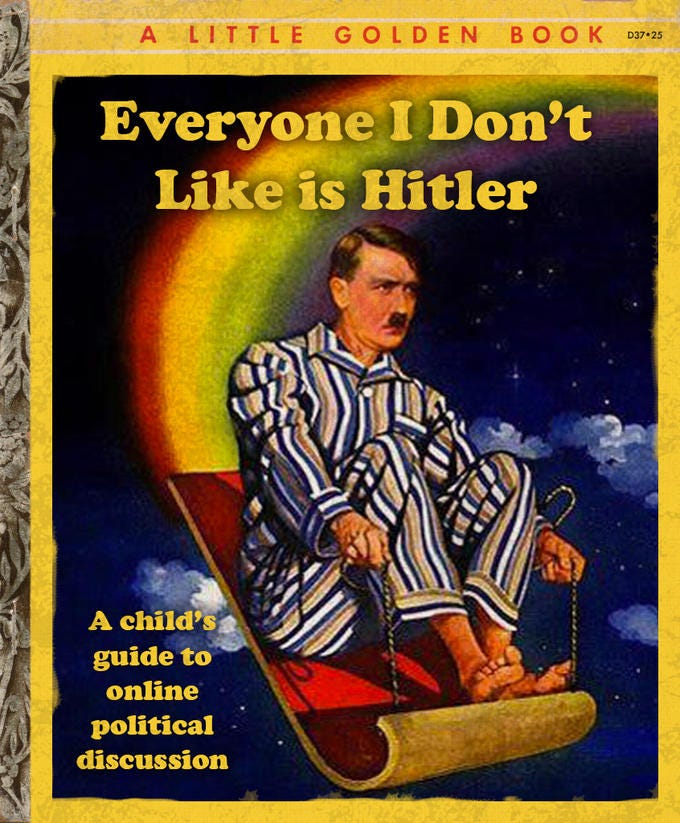

“Ur-fascist is racist, by definition.” How many have debunked shitlibs by calling things they don’t like literally “racist?”

And my favorite, “Our duty is to point fingers at it.” “Justice will be served.” Eco here also advocates the social justice mentality before it became middle class.

Supposedly, Eco only writes books “when he has to piss.”10 I guess the same urge to take a piss is also how he writes about fascism? If fascism cannot have a singular definition, and if any X-amount of traits can be eliminated, “literally everything I don’t like is fascist.” Even if there is one trait, all dialogue and discourse is evil.

This simple comparison of Eco to Gibson goes back to insulting anyone interested in space colonization as fascist. Promethean transhumanism, a crux of classic science fiction, seems unimportant to them. Of course, there is a right kind of “transhumanism” the elites want, and it’s being plugged into the matrix. This is what Gibson stands for.

His neoliberal and egalitarian complaint is justified in one sentence.

“The future is already here. It’s just not very evenly distributed.”

Funny, isn’t it?

On November 27th, 2023, Gibson under his Twitter name “GreatDismal,” wrote this,

“If you don’t vote for Biden, for whatever reason, you’ll be voting for Trump.”11

This tweet alone should show Gibson’s true intentions. This entire time, the worship of Japan is a G7 pyschological operations. “Cyperpunk” aligns with the Malthusian social order, and Gibson will do anything to make sure a corrupted democratic leader stays in office, no matter how irrational he may seem.

Conclusion

I realized something very important about Gibson’s writing style in my late 20s. Classic science-fiction writers tend to explain the logic, the rationality, and the obvious “science,” behind their universe. For Gibson, the structure is laid out with little context. A dystopian future where Japan rules, everyone hacks into computers, and there is a divide between the poor and the corporate class. There is no grand narrative of colonizing Mars. All problems exist on Earth, and the future of science-fiction writing is about social issues. In addition to these problems, the “science” behind cyberpunk is deliberately vague. I know “netrunners” have “icebreakers” that hack into “ice,” but Gibson does not describe how this science-fantasy makes sense. It is up to the reader to fill in the blanks. The imagination of the narrative is more important than the rationality. Cool semantics follow with punk noir attitudes so that the illiterate can be interested in reading a dying genre found only in the print medium.

The pulp description of Neuromancer reads on the back of the first edition,

“Case was the best interface cowboy whoever ran in Earth’s computer matrix. Then he double-crossed the wrong people.”

I am not sure where the “hard science” is alone in this sentence. The Robin Hood adventure is about to begin. It’s a fun one. Nothing more, nothing less. I imagine a thirteen-year-old kid reading this book during lunch break. It breaks my heart that Gibson has become a stooge for the neoliberal oligarchs that decry "fascism" and "those evil Russian hackers" who continue to threaten their racial egalitarian project. When technology becomes the center of a fantasy genre, it’s a sign of our capitalist society.

At the end of the deadpan, existentialist comedy film Napoleon Dynamite, Kip sings an awkward song at his wedding.

“Yes, I love technology

But not as much as you, you see

But I still love technology

Always and forever”

Neuromancer’s absurdity is about the passionate interest in technology, defining our lives. Everyone wants to be a punk computer programmer and escape into anime-futurism. In Napoleon Dynamite, technology is absurd, just like the people of Idaho.

We cannot be defined solely by technology alone. There must be a greater reason to live.

-pilleater

10-28-2021

www.pilleater.com

www.youtube.com/pilleater

https://bio.link/pilleater

http://www.sfsite.com/fsf/2005/cdl0504.htm

http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,1956774,00.html

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/12/16/how-william-gibson-keeps-his-science-fiction-real

https://web.archive.org/web/20190322065716/http://www.williamgibsonbooks.com/source/agrippa.asp

https://www.nytimes.com/1993/08/29/books/the-disappearing-2000-book.html

https://www.spin.com/2019/08/william-gibson-mona-lisa-overdrive-neuromancer-december-1988-interview-new-romancer/

http://project.cyberpunk.ru/idb/gibson_interview.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/09/books/review/william-gibson-by-the-book-interview.html

https://worldpopulationreview.com/canadian-cities/vancouver-population

https://x.com/GreatDismal/status/1728954549170495604?s=20