Future Pastimes: Avant-Garde Board Game Design

The genius design work of Peter Olotka, Bill Eberle, and Jack Kittredge

“Design” in the arts is about the function, the operation, the arrangement, and the aesthetics that are applied to make sense of the art’s interface and purpose. There is controversy surrounding exactly what is “interface” or the concept of “elegance,” considering if these things are needed in the first place. For game design, however, the medium requires an understanding of the interface and play more than any discipline that comes later.

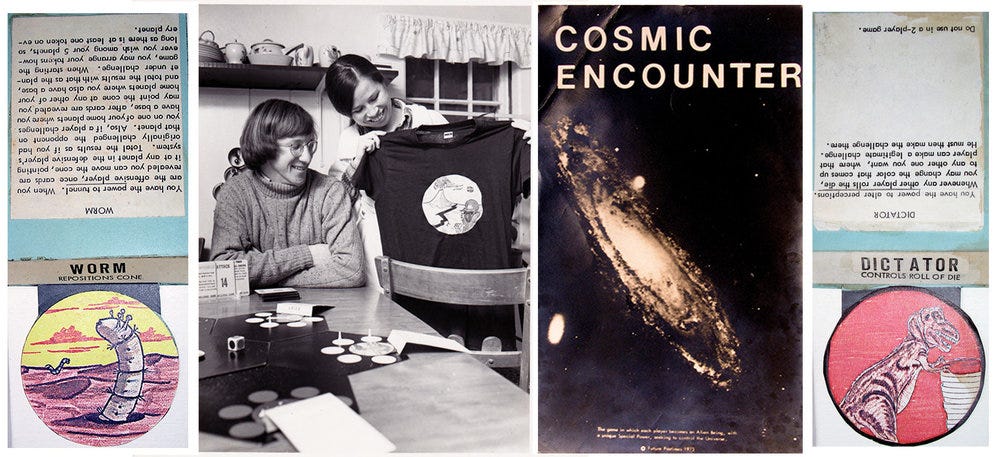

An American game design team known as Future Pastimes has created some of the most innovative and peculiar board games that have changed and even challenged game design as a whole. The team consists of designers Peter Olotka, Greg Olotka, Bill Eberle, Jack Reda, and (then) Jack Kittredge.

If you don’t know the games they have created, they are best known for their 1977 board game, Cosmic Encounter. Cosmic Encounter was one of the first board games, along with Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, to present variable player powers as a design function. While Dungeons & Dragons required a “game master” and players to write out their players with statistics, Cosmic Encounter offered an alternative where players are given a preset character. Then every player acts as an egalitarian game master for the game to function in turn order. Games inspired by Cosmic Encounter range from the ever-changing game master in I’m The Boss by Sid Sackson, to the modular and lottery-winning Killer Bunnies by Jeffrey Neil Bellinger.

The object of Cosmic Encounter is to gain five foreign colonies, where “foreign” means having a “colony” on another player’s home system, as a victory point. While Cosmic Encounter may seem like another basic war game of combat, the catch is that conflict is randomly determined, combat cards are dealt out randomly, player ships are used as wager tokens (think like in Poker), allies are formed and broken, and negotiation and trade are quite common to tilt the game in another player’s favor. Cosmic Encounter takes the best parts of Risk, Diplomacy, and Dungeons & Dragons to create an open-source “modular” system where the design of the game itself can be changed at the whim of the player’s desire during set-up or in-play. Cosmic Encounter works with constraints, while Dungeons & Dragons is freeform.

In essence, Future Pastimes creates game designs that are in the “Oulipo” or even “Dogma 95” tradition of artistic constraints that offer total freedom in all aspects. Peter Olotka stated in his own “Future Pastimes Manifesto”1 that all future board games should have the following traits:

It would have no dice.

No player would be eliminated.

You could have allies or win together.

Every player would be different.

Every game would be different.

You could attack or compromise.

It would not be “of this world.”

“If you can do that, then I can do this.”

And a license to cheat.

These design principles are not just found in Cosmic Encounter, but can also be found in their other games, including Dune, Borderlands, Darkover, TerraTopia, Star Trek E4E, Word Smith, and Hoax.

Peter Olotka and his team addressed a neglected philosophy about the way we think about play and how we artistically express ourselves within the design. Play isn’t just a computer command we follow and submit to, such as reading a novel and following the plot without deconstruction or skepticism of the text.

The Future Pastimes Manifesto is at odds against the design school of “Narratology,” which sees game design as nothing more than a vessel to tell “stories” or to engage in a formulaic, linear story with very little interaction between other humans. Board games excel in human-centric design and eliminate the need for a computer. Computers and technology may help us, humans, to organize materials and equations, but we cannot rely on submissive behavior that makes us feel we are dependent upon solving a boring puzzle with a single, dry solution.

The Meta corporation is currently investing in an artificial intelligence named “Cicero,” which can play Diplomacy at a human level. If successful, we can see artificial intelligence acting like emotional humans while negotiating and talking, rather than acting upon binary formulas and answers. Cicero could play Cosmic Encounter at a human level, opening the door for a new age and the discovery of the importance of human-centric play through robots. Unfortunately, technology is not there yet, and don’t expect this to be out soon. We need to rely on ourselves, rather than the artificial and emulated if we are to learn anything about play and intellect.

The games that Future Pastimes has produced continue to innovate and inspire game designers. There is no perfect game of Cosmic Encounter, as players are always adapting to new game environments, or “synthetic landscapes,” where the answers are never absolute like in chess. Randomness is adaptive, but never centric to play. Winning and losing may be the only binary left, but they also become ambiguous through group wins or the entire party losing. Other human players determine the emotional wager and political vote on how the game can change.

Every game is different, and this modular synth is never boring. Players may add on to the game or connect “the wires” somewhere else. I can make a version of Cosmic Encounter that is unique to me, and I can win the game when things don’t go my way. Rules are only expressive, and not the game itself. Play is the only thing that matters, as we forget what the goals in the game were really about.

The Future Pastime Manifesto is essential to understanding game design made for, and by, the avant-garde artist. The avant-garde artist works with a single medium, or a list of constraints, that can offer unlimited expressions. Dungeons & Dragons may offer us a set of rules, but no one ever agreed that the text was ever universal. Cosmic Encounter is the medium, self-contained in itself, and allows expression with its language. Too much freedom breaks down the system, and we don’t have an expressive language. But a modular system adds words to the language and increases the expression of play, rather than breaking play down to be subjective at the will of the game master in Dungeons & Dragons. Cosmic Encounter is a graphical programming language, while Dungeons & Dragons can fall for the trap of Narratology social control, and ambiguous meaninglessness.

I highly recommend you discover the joy and craft of design through playing Cosmic Encounter and understanding its multiple functions and outcomes. I recommend further reading Uncertainty in Games by Greg Costikyan, The Art of Computer Game Design by Chris Crawford, and Play Matters by Miguel Sicart to understand “Ludology” design against Narratology, and to understand the genius of Cosmic Encounter. The best type of game design is centered around human nature, his ability to express creative play, and his interactions with other humans, not robots.

You can watch a 2018 video I produced about Cosmic Encounter, here at the link, and you can listen to a 2017 podcast I did with the designers, here too.

You can also read about 198 board game reviews I wrote, similar to the design principles of Cosmic Encounter, here.

Finally, if this all piques your interest, you can read about my Post-Elegant Board Game Manifesto, and pick a copy up:

Future Pastimes is more than a small project. It created an avant-garde movement.

-pe

6-29-2023

This article was revised on 11-20-2025.

Cited from his article, “Risk,” from the book, Family Games: The 100 Best (2010), and his article, “Fair Isn’t Fun!,” from the book, Tabletop Analog Game Design (2011).