How Sascha Konietzko Makes Music

A key understanding where all artists should begin

Sascha Konietzko and his “art installation”1 act KMFDM (Kein Mehrheit Für Die Mitleid) has made some of the most influential electronic punk records of all time. This success in creating interesting and original records relies on one creative device that Konietzko has been relying on over and over again; getting a sample and “building out” from there.

Konietzko mentions this technique in the linear notes for the 2007 KMFDM album, Tohuvabohu. He notices that some people start from a guitar riff, a poem to sing, a drum break, or any common origin of playing an instrument.

He writes,

“Working on music, starting a track, writing a song is different for everyone. Some begin with a melody, some with a lyric, some with a groove or a riff. For me, it’s a sound. I am not a virtuoso; my inspiration gets kicked off with something that sounds interesting to me, something I either make or find. Often I simply pitch together a few analogue synths and see what happens. Naturally something will occur, and I record it, then add more to it until an idea begins to form.”2

Konietzko acknowledges that the origin of taking a sample is not well discussed in artistic creation. It’s quite unorthodox to start from a sample and “decorate a tree” to a final song from there. It means that the entire recorded length of time is a eclectic collage of juxtapose meanings, of compare and contrast, where the listener is embracing dance to philosophical pondering.

In a 2007 interview with Ultimate Guitar,3 Konietzko explains this creative process.

“The way it works for me is that whenever I have ideas, I would just jot it down on a piece of paper or something like a matchbook. After a while, I would find things in my pockets, like little stacks of things with ideas totally taken out of context. I have no idea what inspired it or whatever. But that's kind of how it goes. Out of these notes, that's always sort of the stem cell for lyrical ideas or just cool words or cool phrases, stuff that somehow peaks something in my head.”

And like in collage art,

“If you have a guitarist come up with a track, what will they do? They're going to say, ‘Well, I want to do something where I can play a lot of guitar and I want it as fast as possible!’ So when I got the song I was like, Wow, this is really, really cliche in a way. But then I realized, ‘Well, the whole record is really thriving on a lot of cliches and it's really fun there's a really good energy to it.' Then you juxtapose it with the most unlikely thing, a German lyric and it's a very un-metal juxtaposition of vocals.”

In a recent 2022 interview with Fifteen Questions,4 Konietzko writes,

“All of the above provide in some form or another a spark, an idea to further expand upon. Sometimes it’s a noise, something I happen to stumble upon on line or in movie.

When I am not touring I just create audio by playing around in the studio, trying stuff out. Not necessarily on conventional instruments. I have a collection of sparks that I carry around and revisit from time to time.

Also there’s a plethora of sounds in my sample banks from the past 22 albums that sometimes re-inspire me after years of not having heard them.…I have no idea where the “journey” will take me and that’s liberating, allowing me to experiment. Absolutely no preconceived notions.

…There’s a lot (and I mean a LOT) of layering and tracking going on. I like things to be dense and intense.

…Making KMFDM is like cooking. And I cook a lot.”

And in March 2024, Konietzko’s wife Lucia Cifarelli also speaks of Konietzko’s process,5

“We are a bit old-school in our approach… to create a full picture of the artwork… We are not single oriented. Sascha conceptualizes in his mind, like the book ends, beginning of the record, and the end of the record, and then we kind of fill it in with all of these ideas. So it’s more of an experience. I think, we are the kind of band that conceptually lends itself to album-oriented material than just singles.

…We are making music everyday! So Sascha starts his day, goes upstairs in the studio, and starts creating and coming up with ideas, and sometimes those ideas get shelved, and get revisited on a later record…

This origin of “coming up with ideas” could also stem from the creation of Industrial music, of the “white canvas ideology” that advocates art over music. It is right that Sascha says “I am actually not a musician” when this process is applied to what we conceive as “music.”

How has Konietzko’s sampling device become a paradigm in the arts?

It’s not about vaporwave or it’s obsession of talking about noise into literature or academic commentary. That is a Synesthesia fallacy assuming all artistic disciplines belong in the same five senses, because the rebuttal and truth is that the painter is NOT a musician, and the musician is NOT a painter!

The German word “Fachidiot,” or “subject idiot,” is a unique insult, in that the person can be an expert in his discipline, but remains clueless and foolishly indifferent as to how his actions negatively affect other disciplines. How can one person remain so smart and talented in one area (music, painting, writing), and yet be a total idiot in the other?

The American cultural values of “specializing in the market” is an old fallacy that avoids European culture. At one point in time, there had to be specialized individuals to work in a low-tech society and economy. But now in this 2024 post-scarcity society, a man is encouraged to master all disciplines in his own pursuit of intellectualism, against all profit driven ideas. And yet the caveat proposes that “content creation” is superior to all forms of disciplines. This American outsourcing and Philistine behavior against the arts is a warning. The real Fachidiot is the content creator and YouTube actor, pretending to be something he is not to create an entire illusion.

Rather, Konietzko’s concept of the sampling device is found within computer programming.

Object oriented languages, like Max and Pure Data, rely on the programmer “building out” from a single object and following a “data stream” to a final result. This programming is concurrent and happens all at once. In music, sound is recorded to be organized in a linear space of time.

According to Dave Linnenbank in the Bitwig Manual,6

“Unlike sculpture, painting, and architecture, music is an art form appreciated over a defined length of time. That is to say, when we listen to a piece of music, either at home or out at a venue, it unfolds over the same amount of time and at the same pace for everyone in the audience. While music can definitely be performed or created with improvisation, each performance has a rigidly defined structure to us listeners.”

This means that sound is naturally non-linear (that is, vibrations in the air), while music creates a linear space for sound to make sense of it. For programming languages like Max or Pure Data, the function of sound must reach it’s end point to the “digital audio converter” and create sound from there. How that is created is through Konietzko’s sampling device. Programmers start with a single “object” for inspiration, and the object is linked to other objects until a result is achieved. How it becomes music is another issue, as like in a Jackson Pollock painting, programmers start with the “white canvas” and “paint” from there. The execution happens like sound itself, or the flow of a Rube Goldberg machine.

Traditional coding required the programmer to write the code first, and then execute the program when it’s done with the click of the “on” button. An example includes the Japanese puzzle game, Chu Chu Rocket, where the mice have to get to the rocket ship by the help of user’s arrow pads (through programming) and without touching any opposing cats on the way.

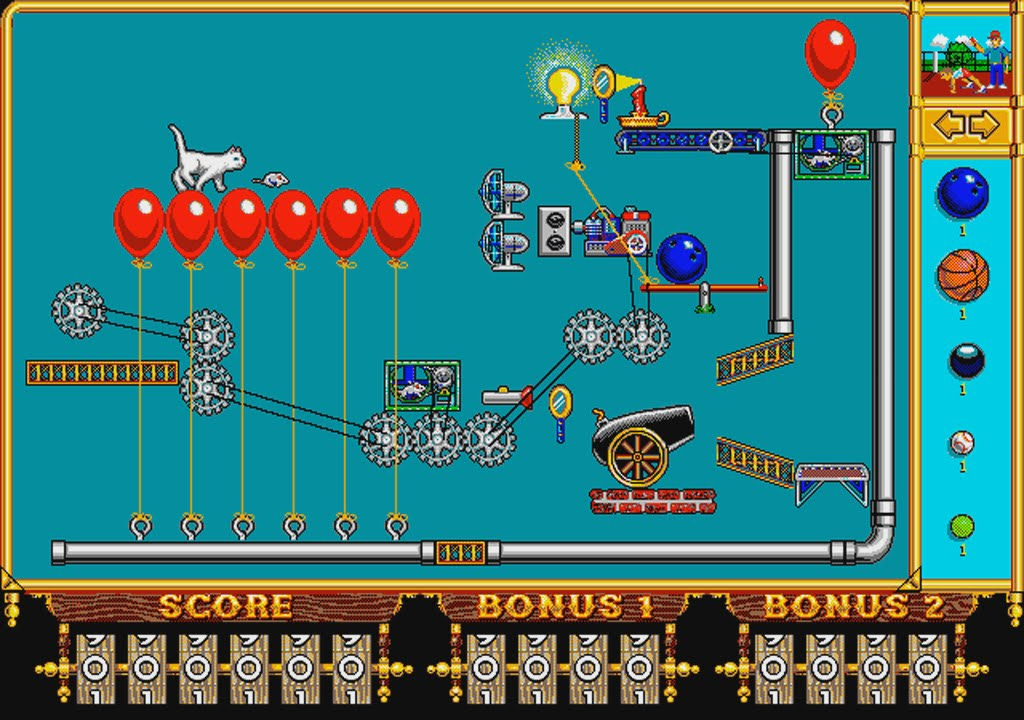

Another set example includes the computer game The Incredible Machine, where the user has to program an actual Rube Goldberg machine to accomplish it’s many tasks. Both programs rely on that single “start” button, just like in Window’s Visual Studio Code or Apple’s Xcode for software programming.

But in Max and Pure Data, everything is concurrent, or “on-the-fly,” happening all at once without any button being pressed. The real “on” or “off” is whether the programmer decides to close the program itself.

It’s like playing a first-person shooter game, where every participate is active, running, and shooting all at once. Quite ironic in Chu Chu Rocket’s multiplayer mode, the competition is concurrent and happening immediately. The programmer has to use skills of adaptability and flexibility in order to get the right results (and to win in the game).

Music making takes on both the set and concurrent programming paradigms. The musician has to constantly press the “play” button to hear where the music is, or in a live performance, the concurrent values of adaptability and flexibility are used to produce the correct improvised music. The studio producer and the concert performer use Konietzko’s sampling device to start somewhere in music creation.

Somewhere between both worlds is the Amiga program Protracker. Although an old program, Protracker starts with a sample, and ends with a song. This is really rare in today’s “digital audio workstations” that emphasize “audio” and not the discipline of music. Protracker forces the user to work with a starting sample he uploads, and “builds out” from there, just like in any programming language that has code upon code. The motivation here is limitation. Protracker only gives the user four trackers, and a limited space of under 800 kilobytes (or close to 2 megabytes if you extend the Amiga’s memory). This creates a “.mod” file, or a program that executes patterns and the samples within.

This self-contained program is different from a .wav or .mp3 file that is recorded audio. By treating music as a light-weight program instead, the musician becomes a programmer. The .mod file can be opened up and the user can see what samples, patterns, and automaton data that has been programmed inside. This is where the programmer can once again, “build out” from a .mod and take whatever sample or pattern track he wants. And just like in Max or Pure Data, these “objects” are copied and pasted, “stolen” by the new user.

While Protracker isn’t concurrent, music constantly is shaped by avid listening and pitching. Even under a concurrent situation, the sound has to be turned “on” or “off” for personal reflection, just like reading a book. All the text is there in a published, physical 100,00 word book. The words are not going away. It’s a matter of whether the user can read the text. In an abstract sense, the book takes on a concurrent space, and we can pick up the text when we switch “on” to reading mode, and “off” when the book is back on the shelf. Existing in life is “concurrent,” but making sense requires that set button. Expression works the same way.

When I dabble in Protracker, I think of how Konietzko start’s off with that first sample, that first idea, and builds an entire program from that single source. Protracker is Konietzko’s sampling device as a program. This is very liberating when you consider what other forms of art one can make with the sample paradigm.

I may be interested in an old pop song, a snippet of political speech, writing in a punk zine, a picture from an exciting event, all of these things create a “novel” experience. While I don’t mean to be a Fachidiot and pretend I am a writer, musician, painter, dancer, and chef all at once, I realize each of these artistic disciplines would benefit from a sampling device.

Listening to every single song KMFDM has ever made, I have to spot the origin sample, and realize that the tree which as been decorated is meaningful in many ways. The artist keeps putting things on the white canvas like objects in Max or Pure Data. It’s not structural, but rhizomic. The many meanings and origins of artistic intentions are buried in layers of improvisations, connections, and nonsensical relations to create a final product. Nothing is truly a single ideological stance. Ideology can never take over art because it can’t comprehend the sampling device that Konietzko has explained throughout all these years of KMFDM. Trojans and “culture war” can’t exist within art.

That, in my opinion, is true Industrial music that advocates the nature of eclecticism, collage, and juxtaposition. Art works in this same way.

-pe

4-9-2024

“What Do You Know, Deutschland?” linear notes. Z-Records, 1986.

Tohubabohu CD liner notes. 2007.

An Interview with Lucia Cifarelli (KMFDM) - We Go To 11 - March 8th, 2024 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7FdVPyydHOE).

For version 4.1, November 2021.

kino phrase: "This means that sound is naturally non-linear (that is, vibrations in the air), while music creates a linear space for sound to make sense of it."