Patalliro!: The World's Most Controversial Anime

And why it's my favorite anime of all time

Patalliro! is my favorite manga and anime ever, yet when I bring it up at house parties or art gallery events, no one seems to know what it is. And it’s unknown for a good reason.

Patalliro! is one of Japan’s longest-running manga ever, with over 100 issues penned by the eccentric creator and artist himself, Mineo Maya. It was also the first anime to debut the shounen-ai genre, or, the the first ever openly homosexual anime. It also includes cross-dressers, trans people, Satanists, monsters, Neo-Nazis, pedophiles, David Bowie impersonators, and many more John Waters-style queers running amok. Starting in 2013, only 43 out of the 49 episodes have been translated by the fans, especially by the work of Emeryl and Lemur7 over at the secluded and fringe Aarinfantasy forum. And to this day, there is no official English translation of the Patalliro! manga.

Meanwhile, a new Patalliro! 40th anniversary DVD box set was released earlier this year in Japan only. Even Metal Gear Solid’s Hideo Kojima wrote in a recent tweet,

“I bought "Patalliro!" BD-BOX to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the animated series. "Zombie" is 45 years old, and "Patalliro!" is 40 years old. Is this a 2-disc set with all the episodes? Kazuyuki Sogabe's Bancoran is cool. The ending music is also nostalgic.”

So why was it never translated for the West? The plot, theme, script, and aesthetics are wildly offensive. Frederik L. Schodt in his book Dreamland Japan has mentioned the success of Patalliro! being something exclusively happening in Japan, and not faring well with the West. The Japanese live-action movie just came out in 2019, along with another live-action recreation of another Maya manga, Fly Me to the Saitama, becoming at the time one of the highest-grossing films in Japan. Mineo Maya is a popular Japanese icon of the same status as Osamu Tezuka or Akira Toriyama, so why isn’t he noticed in America? If JoJo's Bizarre Adventures became popular among the American queer fanbase a decade ago, why not Patalliro!?

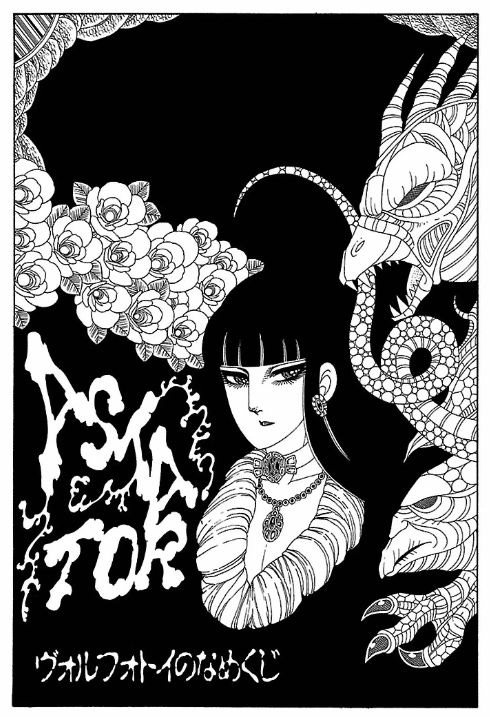

There are many good reasons. But ultimately I think the reasons why is because of pedophilia, its unapologetic nature towards fascism, hedonistic cross-dressing and rape, extreme Japanese chauvinism, and an aesthetic that screams the pagan motorcycle art direction advocated by Boyd Rice, Shaun Partridge, Jim Goad, and Simon Bisley, along with the backdoor queer mutilation collage art of Dennis Cooper, Peter Sotos, and Edmund White. Patalliro! is for bad boys, and Maya’s aesthetic could be described as Harry Clarke or Aubrey Beardsley meeting gay Japanese men overcoming child abuse and getting into rock ‘n roll satanism as a cope. I wouldn’t be surprised if Maya was also a fan of Yukio Mishima and Akihiro Miwa’s 1968 cult movie, Black Lizard.

There is hardly a proper English biography of Mineo Maya that exists. I have some of his biographies in Japanese, and at one point in his life, he was a cross-dressing waitress and dancer (as expressed in a book about his love for Salvador Dali). Already that screams of liberal fascination around trans people, and to underestimate Maya as an important figure is perplexing. He has three children and continues to draw and release the new Patalliro! issues at 70 years old.

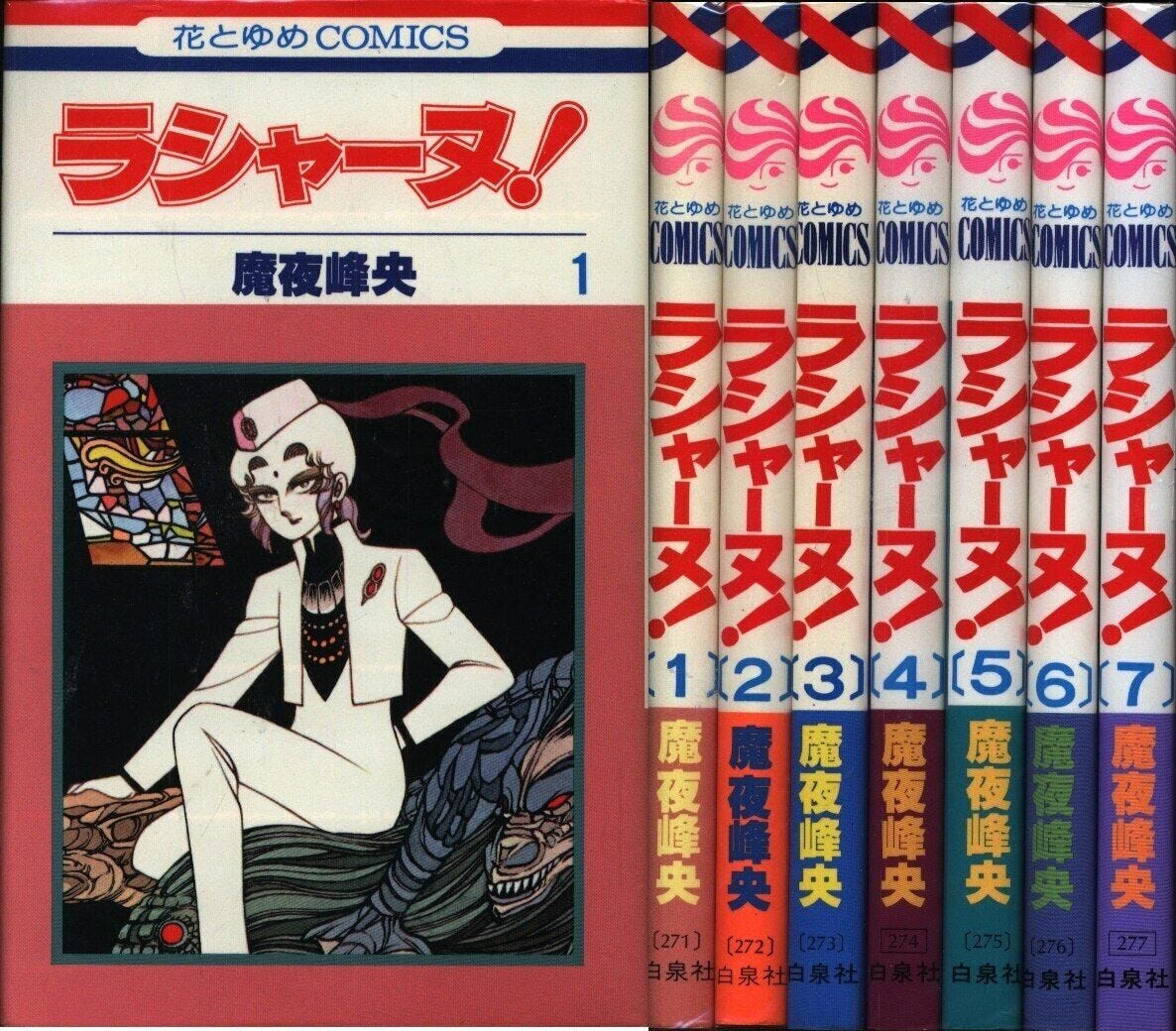

Maya’s other mangas are aesthetically pleasing to the dark and queer pleasure. Such include Cherry Boy Scramble, about a cross-dressing boy who is desired by all the militant and fascist students, Astarot, about a shapeshifting demon investigator from an H.R. Giger hell who solves mysteries around other pretty boy slaves, and Rashanu!, a gay, hedonistic Japanese Hindu who’s into Esoterica while exposing Pizzagate elite parties. Many themes include post-traumatic stress disorder, child abuse, arousal of the unknown, and forbidden desire. And both young Japanese boys and girls, along with adults, enjoy Patalliro! in 2023.

The plot of Patalliro! is about a 10-year-old dictator in the fictional kingdom of Malynera. Jack Bancoran, a special agent from MI6, must protect Patalliro, as there is a shakeup in his kingdom. Bancoran has the power to look into a boy’s face and sexually seduce them for selfish gain or political control. He soon falls for Maraich, an abused, cross-dressing trans person who works for the International Diamond Syndicate, a Neo-Nazi Satanist crime organization. (There’s also a great scene in the first Patalliro! movie, The Stardust Project, where the bad guys all do a sieg-heil in their esoteric hideout). Bancoran and Maraich soon fall for each other while other eccentric one-shot stories happen.

…And let’s just say Maraich soon gets pregnant eventually with Bancoran’s child. Yeah, it’s out there.

While the manga is preferred, the anime is the magnum opus. Everything from episode one should be enough to entice you into this transgressive, artsy world. The synthpop soundtrack is fantastic and was also released multiple times on vinyl. Even watching Patalliro! on mute, the art nouveau style captures your attention, as episodes could be screen projected on the wall at a loud, e-girl club venue in Bushwick, Brooklyn.

Spin the visuals with tracks by Xiu Xiu, Sandii & the Sunsetz, and Yukihiro Takahashi, and you got it. It goes so well! Just taking still screenshots of the anime, you are left with a sublime sense of beauty that reaches the same sadistic heights as the 1973 Japanese animation, Belladonna of Sadness.

You can still buy the original Patalliro! animation cels on eBay, which in turn might become even more expensive twenty years from now. From time to time, I’ll search eBay out of the blue to catch up on vintage Patalliro! memorabilia. I have a little space where I keep all my Patalliro! stuff, and I take pride in it.

I believe Patalliro’s gender queer pride could influence the hip and burrowing white Americans who are looking for cosmopolitan interracial relationships and marriage in a big city. It’s a coming-of-age romance that can empower the meek and mild suburban teenager looking for answers. In a way, Patalliro! celebrates the fusion of Eurasianism under a punk subculture, where the inclusivity is inviting like the show’s sexuality. It’s a blueprint for a hybrid “East meets West” high art culture.

René Girard once wrote that “mimetic desire” is the main principle to the creation of the arts and the emulation of the good life. Patalliro! becomes a represented role model, in that viewers emulate its aesthetics and themes, and project the anime’s values into their own lives. Dick Hebdige also summarized these causes and effects in his study, simply called subcultures. Patalliro! becomes its subculture, and its influence in the West is based upon this notion. Call it ironic or “meta,” this is how Akira impacted America’s interest in William Gibson’s concept of cyberpunk in the late 80s. Patalliro! is doing the same with “transgressive liberalism” and its flirtation with homosexual sadism and homofascism subculture in the 2020s. This is likely the reason why Patalliro! is not fully accepted, as the older generation tends to find the Japanese interest in boy love “problematic.”

In Episode 4, around the 7:52 time mark, Patalliro calls Bancoran as he’s in “the middle of his work.” That “work” is him cuddling and possibly making out with an underage boy. Not only is it a homosexual fantasy, but a real pedophile fantasy too. How could the normative world accept this behavior?

Like Ryan Trecartin superimposing the fakeness of teen worship and short attention span gossip in his 2013 film Center Jenny, we develop a feeling of disgust watching Jenny the same way we see manufactured pedophilia through child star fandom, unknown to its creator and the viewer. The Disney Channel, while targeted toward innocent children, celebrates “pedophilia” through its corporate inauthenticity and visual effects. Through sincerity, Patalliro! embraces this twisted form of homosexuality as a reflection of individual queerness found in Japanese culture.

This is a fine line difference between Japanese viewers the passive American viewers. While the Japanese watch without remorse, the average American can never decode the visual culture in front of them. Or like in Larry Clark’s short film Impaled, we may develop disgust when we realize how sincere these people are, but in reality, this is normal to them. The Japanese embrace Patalliro! like a pornographer does in his routine.

As another example of transgressive art, Robert Mapplethorpe’s Man in Polyester Suit is a photo of a black man with his penis out. Consider transgressive culture in the 1980s and how different it was. By 2023 standards, this photograph can be offensive to both white and black liberals who observe that Mapplethorpe is projecting racial stereotypes and is profiteering off of art world gentrification. However, and ironically, the equivalent photography of Antoine d'Agata is widely accepted instead, as his themes around “darkness” and hedonism are not the same as Mapplethorpe’s interests. Mapplethorpe is old news, and D’Agata is in. Perhaps the popularity of Patalliro! can never be realized in America because of its touchy subjects of perversion, rape, and racism (especially the Patalliro! ending credit song Cock Robin, which celebrates Japanese imperialism over Korea).

The liberal elite pick and choose their art direction based upon zeitgeist whims. Patalliro! was ahead of its time and is still outside liberal sensitivity.

So why still read or watch Patalliro! now? It never lost its popularity in Japan, and there is no denying its Japanese interest. Japanese children love it as much as adults do. Hideo Kojima loves it. The guy from X Japan is named after Patalliro. It has a huge influence there. While Hirohiko Araki’s art is celebrated for being esoteric, why not Mineo Maya’s?

Patalliro! is evil, perverted, witty, esoteric, and smart. It expresses sadism in an ethical way, where the reader becomes self-enlightened through their understanding of personal traumas and sexual moments. Patalliro! isn’t just for women, but for Platonic men that have repressed desires and abusive parents. We can never overcome trauma, as trauma haunts us like a ghost.

Mineo Maya’s artistic expression helps us see the demons as angels, and provides us with a subculture that is akin to martial industrial, creating collage art of the abused with the political. The rhizomatic connection between the liberal and the anti-liberal is possible in the same way one can be openly gay and fascist.

The dark European nature of the 1970s child abuse established in Kaze to Ki no Uta is only exacerbated in Patalliro! towards a Lady Divine level of outrage. Power is given to the male reader who wants a dream world where political correctness becomes John Waters’ “political erectness.” Mineo Maya is a Japanese chao magick magician and Patalliro! summons the same magic techniques used by William S. Burroughs.

I highly recommend watching the anime first and then taking a dive into the manga found online. I hope one day that an American publisher will provide a proper English translation of the text, along with a brand new English dub for the anime. I guarantee the Americana audience will be a bohemian one, not afraid to die under political pressure or censorship.

Patalliro! is an intellectual attitude, and not just generic pornography to dispose of. It is intellectual pornography and avant-garde art of the highest degree that deserves to be labeled as one of the greatest anime of all time.

-pe

6-28-2023