The Importance of Fort Thunder

The venue, or space, becomes the ideology and purpose, not the "show" playing

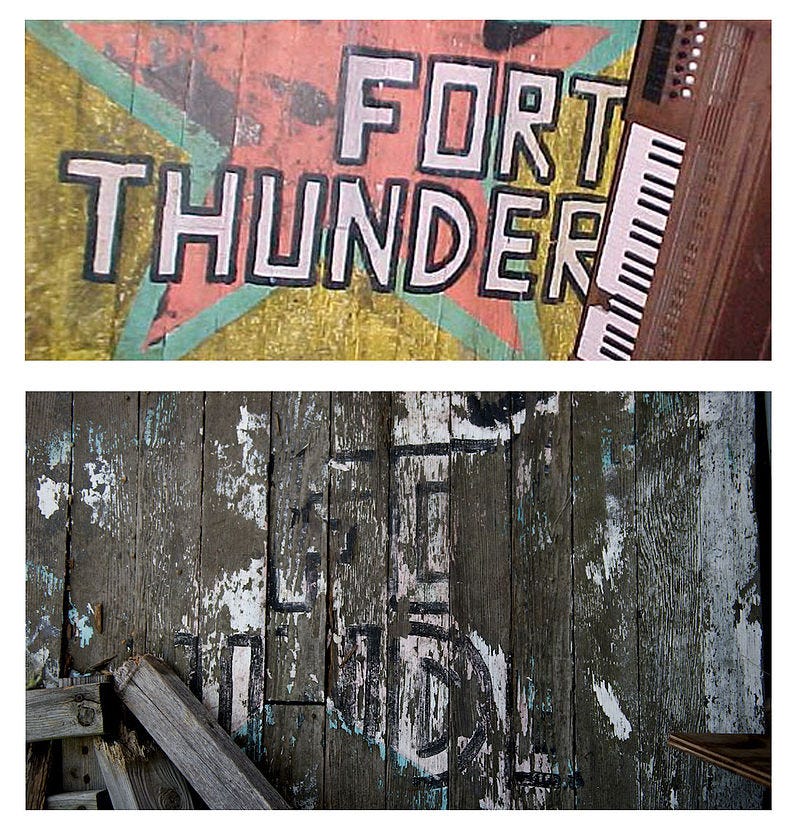

Fort Thunder was an art commune, punk venue, and squatter space for students and residents of Rhode Island School of Design that lasted from 1994 or 1995 to 2001. That’s a quick seven years of punk shows, experimentation, art display, hangouts, parties, and workshops in a neglected warehouse that was turned upside down. The project was started by two upper-middle-class white boys, Mat Brinkman and Brian Chippendale. Brinkman later tried to resurrect Fort Thunder through Hilarious Attic, but only lasted from 2002 to 2007, and Chippendale started both bands, Mindflayer and Lighting Bolt, as Fort Thunder projects.

Chippendale is responsible for all of Fort Thunder’s aesthetics, art direction, a noise rock genre of “Thundercore.” He is a pioneer for the millennial generation’s interest in “punk” style basement “shows,” “all ages” house parties, and the future squiggle art styles of Michael DeForge, Benji Nate, Patrick Kyle, Katie Skelly, and further has influenced Thundercore-style comic stores, like Partners and Sons out of Philadelphia, that continues Chippendale’s tradition of the hoarder commune.

How do I describe the aesthetic of Fort Thunder in detail? Imagine the 90’s fad of indoor playplaces for children, kind of like Rainforest Cafe, Discovery Zone, or Leaps and Bounds. Now imagine Fort Thunder as being that kind of indoor play place but for twenty-something art school students into DIY punk music and fashion design.

Many copycat venues also started popping up after 2001. Some include Philadelphia’s Big Rock Candy Mountain, New York City’s Rubulad, San Francisco’s Noisebridge, Santa Fe’s Meow Wolf, and Phoenix’s The Trunk Space. In my own Queer Culture pamphlet, I tried to list a majority of “ask for an address” east coast punk venues, and listed them as “cool punk house names.” My intention was for readers to go out looking to attend these venues or learn about their history. The action of going to someone’s private house for a “show” can be a queer experience.

Some of these goofy, and real, venue names include,

“The Parlor, Moo Moo Farm, Maxwell’s, The Wetlands, The Sound Hole, Pi Lam, Knitting Factor, 14 Livingstone Ave, The Fire, Lions Den, Be Happy House, Anarchtica, Bowhouse, Legion of Doom, Your Mom’s House, Junkyard Palace, The Cake Shop, Confetti House, The Gasthaus, Castle Greyskull, Danger Danger Gallery, Nimrod’s Castle, Terrordome, Hank Hill Residents, Salamander Icefort, Super Happy Funland, The Trunk Space, Secret Squirrel, Meemaw House, The Den, Asterisk, The Crackhouse, The Lo- fi Social Club, Blue Carpet Garage, Meat Town USA, Shady Retreat Road, Candy Land, The Punk Porch, Mr. Roboto Project, Silent Barn, The End, Duck in a Stack, Ground Zero, Haunted Kitchen, Friendship City, The Radio Room, Spazz Haus, The Fort, Monster Island Basement, Corpse Fortress, Sugar City, Beer Can Garden, Skull Alley, Spaceland, Black Cat Backstage, Goo Lagoon, Magic Stick, The Hideout, Stone Pony, The Bottletree, Club Downunder, Mohawk Palace, Captain’s Rest, Hilltop Zone, The Aquarium, Wonder Root, The Trainyard, No Fun Club, The Bruce Willis, Circuit City, Grog Shop, The Stanhope House, Ace of Cups, Club Dada, The Bug Jar, Borg Ward, Neurolux, The Mothlight, The Ruins, This Ain’t Hollywood, House of Vans, Lizards Lounge, Cat’s Cradle, The Cactus Club, Ice Pyramids, World Trade Slayer, Fuck Mountain, The Unifactor, and 69 Louis Street.”

All of these names, aesthetics, and venue purposes are to serve the interest of Fort Thunder and the legacy it had in the 2000s period. The popularity of the band Lighting Bolt is associated with the nostalgic memory and sound of the Fort Thunder scene.

And if you like the aesthetics and humor of Tim Heidecker, Eric Wareheim, Sam Hyde, Frank Hassle, or Beardson Beardly, it should come as no surprise that Hyde was an alumni of RISD, and thus being influenced by Ryan Trecartin and emulating the absurd nature of what is called, “hyperpop.” The origins of the RISD art movement were never an alt-right thing, or hipsters trying to be reactionary, but all of it comes back to Fort Thunder, an Epicurean experimental space in Providence.

At Fort Thunder’s closing in 2001, the anarchist book, Days of War, Nights of Love, wrote a eulogy on page 204. The following reads:

“CrimethInc. collective in Providence, Rhode Island opened the first Crimethinc. compound, known as Fort Thunder. The space is operated by a core of people who inhabit the building, working in co-operation with the surrounding community, for which the compound provides a shared place for all sorts of projects: a Food Not Bombs kitchen and cafe, a music and reading library, a free bicycle bank (operating in conjunction with other bicycle exchanges around the city, thus providing free and environmentally individual transportation for the community), an artists' workshop, a public darkroom for photographers, a practice/performance space for movie screenings, plays, and talent shows, a communal child care facility, even a sauna-all open to the public, of course, and organized with them at consensus meetings. Special events have included everything from underground film festivals to a mock Roman gladiator competition, complete with a spinning cage and screaming crowd. In the years since numerous similar compounds have been opened across the world (see illustration for sample floorplan). These spaces allow us Crimethinc. workers to survive with mini- mal "living expenses," and to link our welfare to that of others, rather than taking care of our own needs at everyone else's expense, as we're all expected to do.”

“CrimethInc” is the anonymous anarchist publisher and movement. This eulogy is not faithful to the original vision of what happened there, as CrimethInc wants to cover up Fort Thunder as merely being a part of a bigger religious movement of Epicurean anarchist living. But what is acknowledged is that Fort Thunder was a “first” of its kind. If we follow the logic of the lifestyle anarchist, we realize that the funhouse-hoarder punk venue, like Fort Thunder, is a recent invention of the last three decades. It could stem from the popularity of The Flaming Lips or the outrageous costume wrestling events of Kaiju Big Battel, but whatever form it takes, from “mock Roman gladiator competitions,” “a free bicycle bank,” or “Halloween mazes” of sorts, the theme of quirkiness and playfulness of being a teenager that never grows up is apparent here.

The importance of Fort Thunder does not lie in the fact it’s a bourgeois anarchist (and very white) movement against capitalism or modern society but as a recent invention on the Epicurean idea that the “space” or “platform” is more important than the artistic act itself. The concept of the post-World War II language of the French “collective,” or the Stalinist era “youth movement” are also recent inventions rooted in this militant language. In an age that Émile Durkheim labeled us as “deracinated” from authentic living under capitalism, we look for byproducts of culture under profit-driven consumption, or “subculture,” that gives us an artificial meaning constructed for an individualistic liberal ideology. “Property” becomes the center of our materialistic reality, and our primitive and natural urges are then associated with ownership, fashion, and belonging. We start to believe we own the artificial construct “Fort Thunder,” as a name, space, and ideological movement. And whoever is ridiculed as an associate of Fort Thunder, we take offense and must defend the religious movement from outsiders.

…At least this is the anarchist understanding of the meaning of Fort Thunder. Only 160,000 people lived in Providence during the 1990s, and around 70% of that population were white. That's around 112,000 white citizens. This is important because when Fort Thunder was lawfully demolished in 2002, there was a complaint about “gentrification”1 in Olneyville, the so-called “poorest neighborhood” in all-white Providence at the time. This is where Fort Thunder was located.

What exactly was “gentrification” when well-to-do white art students started a stuff-white-people-like art commune already within walking distance of an expensive art college? Perhaps Olneyville was home to Hispanics, where the commune could be expressed by whites with a racial group that could be sympathetic to their aesthetics. But again, there is nothing more obnoxious than the white hipsters that started Fort Thunder, and cry to themselves that they are responsible for the horrible racism of simply wanting to express a bourgeois workshop next to sympathetic non-whites. And like any other Christian church, American Christianity always bends over to kiss the boots of those who could see the light of imperial liberalism. As Joseph Conrad would say, “the horror!” Would it make any difference if they did it in a black neighborhood? Fort Thunder likely wouldn’t exist.

Jeff Schneider was the guitarist for the casual Fort Thunder band, Arab On Radar. In his 2018 autobiography about himself and the band, “Psychiatric Tissues,” Schneider makes similar conclusions about the RISD elitism of Fort Thunder.

“Fort Thunder was an amazing place, in through the parking lot, Dunkin Donuts on your right, all the way back. The door was on the ground level, an inconspicuous door to a mill. If you were really insane, once shows started, you could go up the rickety rusted fire escape staircase inside left right, the stairs made creaking sounds reminiscent of an old boat, the sound only wood could make. Then on the left was the door to enter. A wanderlust of art from the minuscule to the large hung everywhere, it was an installation in itself, posters, bikes, stickers, GI Joe figures, lots of Legos. Right when you walked in there was a narrow corridor, prior to it opening up to the full loft.

This is where Ben McOsker or Brinkman would be sitting in the hall with a large plastic Halloween pumpkin or sometimes just a beer box collecting donations. People would throw in some cash. I always contributed, stupid fuck I was, but it was an ethic thing, people who don’t support shit on this level can go fuck themselves.

The irony of this mill building, where the oil soaked into the wood floors, blood, labor, sweat, toil of the poorest, now was that it was occupied by the elite’s kids going to the best art schools in the world and their Ivy League friends. This was not in my thoughts much back then thought.

…But this ignorance was rampant at the time, too much privilege…”2

There was even a “Fort Thunder look.” According to Schneider,

“…There was a well-established ‘Fort Thunder look’ which consisted of recycled clothing, patches, dirtiness, custom-made t-shirts all that art school stuff at the time. Chippendale, Brinkman, and a few others at the Fort consciously, and to this day, maintained a hair-do that was unique, it was cutting your own hair, presumably without a mirror, at least at first, just hacking away, which produced an uneven and chopped up mess, but ultra-cute in the right critical settings, it added art credibility to their mere presence.”3

And Schneider felt the RISD connection was a huge part of the influence,

“Playing with Lighting Bolt, man, they had a marketing sense, what we called “the RISD Bat Signal,” they sent out a message at the 11th hour, and hundreds of people would still show up, scarcity, they knew how to harness that shit. I wonder if they teach this at RISD? It reeked of elitist mentality, country clubs ran on this energy, but then again, they were really damn good. …I have to admit we were totally jealous, in case that’s not obvious.”4

Whenever we talk about the lasting influences of Wes Anderson films or Napoleon Dynamite as crucial expressions of white aesthetics, Fort Thunder played that leaning role towards SWPL activities of late Gen-Xers and making them fashionable, like having an interest in “alternative” comics, noise rock, and art films. We are both doomed and loved by these bourgeois influences in the independent arts post-1990.

Tom Spurgeon of The Comics Journal wrote his immediate tribute, “Fort Thunder Forever,” in the 2003 issue (or number 256). His historical explanation of how the American comic turned over to the Thundercore aesthetic is important to understand.

“Arts movements require proximity and a shared outlook. Comics has long been big on the first and not so hot on the second. Since the medium's cohesion into an active artistic outlet late in the 19th Century, cartoonists have frequently huddled in the same place. Early cartoonists were bound by their common identity as newspapermen, and many spent at least some time in a bullpen working elbow to elbow with their peers. The early comic book industry was dominated by New York City, and if you squint, the stories of studios being thrown together and artists working on each others' pages sound like the beginnings of the kind of back and forth that galvanizes certain approaches to the form. But commercial concerns didn't merely override more ambitious concerns; they steamrolled them. More importantly, these were not the kind of commercial concerns that left much if any room for artistic expression.

After a few decades, as industry relationships deepened and mail service improved, more comic-strip cartoonists and comic-book artists began to drift back into their natural state of self-isolated productivity. Many of the strip artists began slinking down to Florida after World War II while a big cross-section of working comic-book people would eventually move West. Later, artists and writers entering the industry could avoid moving to New York City altogether. The underground-comix cartoonists of the 1960s shared geographical close quarters (most were in the Bay Area, or spent some time there) and a resistance to corporate expressions of and limitations to art. They remain the closest thing comics has to a recognizable true movement. The idea that sharing between peers might be valuable has been echoed in most recognizable groups of cartoonists that have popped up ever since -- from the bearded, ball-capped second generation at Marvel and New DC to the Seattle Story Ark crowd of the early to mid-1990s to what I'm assured are close-knit smatterings of burgeoning talents in St. Louis, New York City and Los Angeles today.

Fort Thunder was different. The Providence, R.I., group has achieved importance not just for the sum total of its considerable artists but for its collective impact and its value as a symbol of unfettered artistic expression. In terms of ambition, skill and the ability to bring together vaguely like-minded artists and present them as an artistic whole, Fort Thunder was closer to something like the French publisher Le Dernier Cri than anything in American comics. Yet much in the way they presented and carried themselves reminded less of a European-style arts scene than it did a local crew of skateboarders, or maybe a regional recording studio with a loose, rotating stable of bands. Fort Thunder not only existed in several artistic worlds at once but managed to exist only in those worlds' best parts for an impressive length of time.

The key to understanding Fort Thunder is that it was not just a group of cartoonists who lived near each other and socialized. It was a group of artists, many of whom pursued comics among other kinds of media, who lived together and shared the same workspace. As an outgrowth of the Rhode Island School of Design [RISD] where nearly all of them attended (some even graduating), Fort Thunder provided a common setting for creation that imposed almost no economic imperative to conform to commercial standards or to change in an attempt to catch the next big wave. They were young, rents were cheap, and incidental money could be had by dipping into other more commercial areas of artistic enterprise such as silk-screening rock posters. Fort Thunder was also fairly isolated, both in terms of influences that breached its walls and how that work was released to the outside world. This allowed its artists to produce a significant body of work that most people have yet to see. It also fueled the group's lasting mystique. The urge -- even seven years after discovering the group -- is not to dig too deeply, so as not to uncover the grim and probably unromantic particulars.”

What Spurgeon points out, is that the 1990’s transformation of the comic began with the economic incentive to “do-it-yourself,” and to use comics as a self-expression medium than following any standards or narrative rules. The money came from a trust fund and carelessly was spent to have fun. Significantly, space played a huge role in a collaborative effort. Fort Thunder became an American Situationist International, where lowbrow cartoons and post-psychedelic music became the theme under an anonymous label. It’s not about what Mat Brinkman, Brian Chippendale, or any individual did, but what was more important, was the stories and events that people experienced under the seven-year tenure of Fort Thunder. The space became the ideology of the art, and not the art itself.

According to Spurgeon, Mat Brinkman also liked the idea of a “Fort” where "you're there to defend yourself from the quietness of American bullshit."5 This militant idealism is principled through the ideology of the space itself. The Peter Pan childhood escapism is stated again, that, “Fort Thunder was a place where the aspects of adult life unnecessary for sustained artistic output could be kept from walking through the door.”

Spurgeon also addresses Fort Thunder’s legacy in comics,

“Fort Thunder's bigger influence may be in their ability to let cartoonists see beyond very narrow expectations of what comics should look like. When it comes to helping the second and third generations of alternative cartoonists see beyond previous constraints, it's difficult to separate the influence of the Fort myth and the impact that the comics themselves have enjoyed - but exposure to either deepens the feeling that any set of influences, any approach to art, has the potential to become compelling work. This is the same set of feelings that many discover and explore through doing a 24-hour comic or jamming with other artists, just without the rules and inherent game-play. Fort Thunder has told artists and readers there is nothing stopping any comic from being good except the work itself.”

And,

“The desire to keep working, to keep busy, should serve all the Fort Thunder artists well in future years. The loss of the space, either by leaving or being asked to leave, has brought with it major adjustments for many of the members as they negotiate either side of 30 years old. Living in the Fort not only allowed many of the artists a chance to work and refine their talent, but it suffused those efforts with a meaning larger than any single project: "There was an energy level that was built up," says Brinkman. "It didn't really matter what you were working on. It could be the dumbest little thing, but it felt like a bigger thing." There are other undeniable changes as well - a new family in at least one case, Forcefield's apparent dissolution over disagreements on what to do after the Whitney appearance, questions of how much energy should be devoted to pursue new directions and how much to perfect and refine artistic paths traveled thus far. While the mini-comics and collections contain startling works, to a large extent they represent a promising direction that has yet to be fully pursued. The weakest part of Fort Thunder's legacy to comics may be the individual comics themselves, something asserted by several cartoonists replying to questions for this article. Although there are no guarantees, the basic interest in all of the artists to keep working, specifically on comics to varying degrees, is all an audience can ask for. With a readership slowly settling into place that can perhaps better appreciate the artistic avenues to be explored and an infrastructure that should allow for any books to remain in print indefinitely, one has every reason to hope that greater works lie ahead.”

I cannot help but think of similar anarchist wisdom on production found in Days of War, Nights of Love, the same book that advocates Fort Thunder as an ideological anarchist collective. The page reads:

…Spurgeon believes that the quirky, playful, and childlike nature of Fort Thunder came from the aspect of always being busy without a care for who and what art is for. Miguel Sicart made a similar argument in Play Matters, where the activity of “play” becomes the focal point of game design and artistic expression. If the action of anarchy requires careless production, so too can we adapt to “doing” without consumption.

We often see mainstream and popular acts play in expensive concert halls and venues, but the experience becomes different when we attend that same experience in an intimate setting, or the band playing behind a dumpster. Even punk posters have their artistic genre. The cliché notion that the event is an “all ages” show, followed by absurd band names based upon popular culture or generic sounding domain grabs without legacy. We tend to care more about the experience sometimes than the band that is playing. This is akin to going to a bar or nightclub, acting upon hedonistic desires, and meeting eccentric strangers. Fort Thunder might as well be that hedonic fort full of eccentric strangers and nonsensical teenagers not willing to grow up.

The criticism I present is that the future art of comics, music, punk, indie, poetry reading, theater, DIY spaces, and white people aesthetics all come back to a short-lived art project that an entire generation never experienced before until then. Fort Thunder became the crux to the understanding of what a bourgeois “art commune” or “punk space” is. All future “spaces” and inner-city “platforms” emulate Fort Thunder’s hoarder aesthetics and playful principles. There is no universal way of playing “a show,” as it was mere emulation and mimicry, by word of mouth and action, among twenty-something artists who didn’t have a shot at Hollywood or publicity. While the punk house venues of the 1970s to 80s were most edgier and dangerous, Fort Thunder by the 90s turned the punk venue into a “safe space,” or an Epicurean society that focused on resurrecting hippy values of the 1960s.

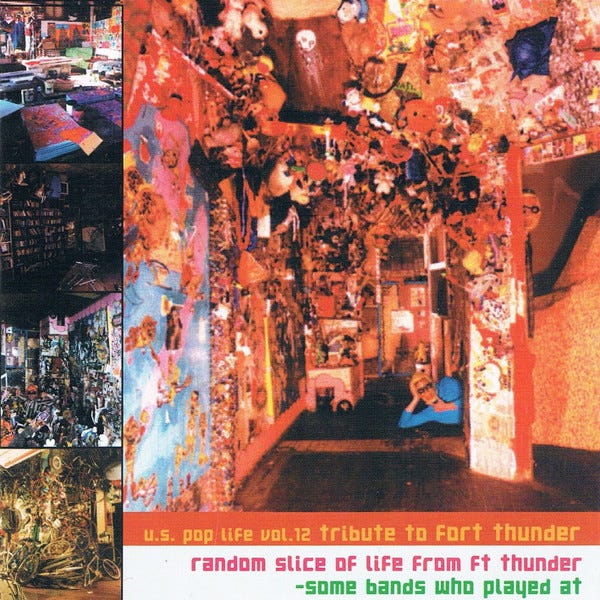

Memories of Fort Thunder are brought up again once in a while. Its first tribute was in 2001, compiled as “Tribute to Fort Thunder,” by Contact Records.

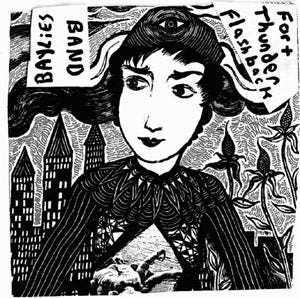

In 2009, the Providence act, Baylies Band, released their album, “Fort Thunder Flashback.”

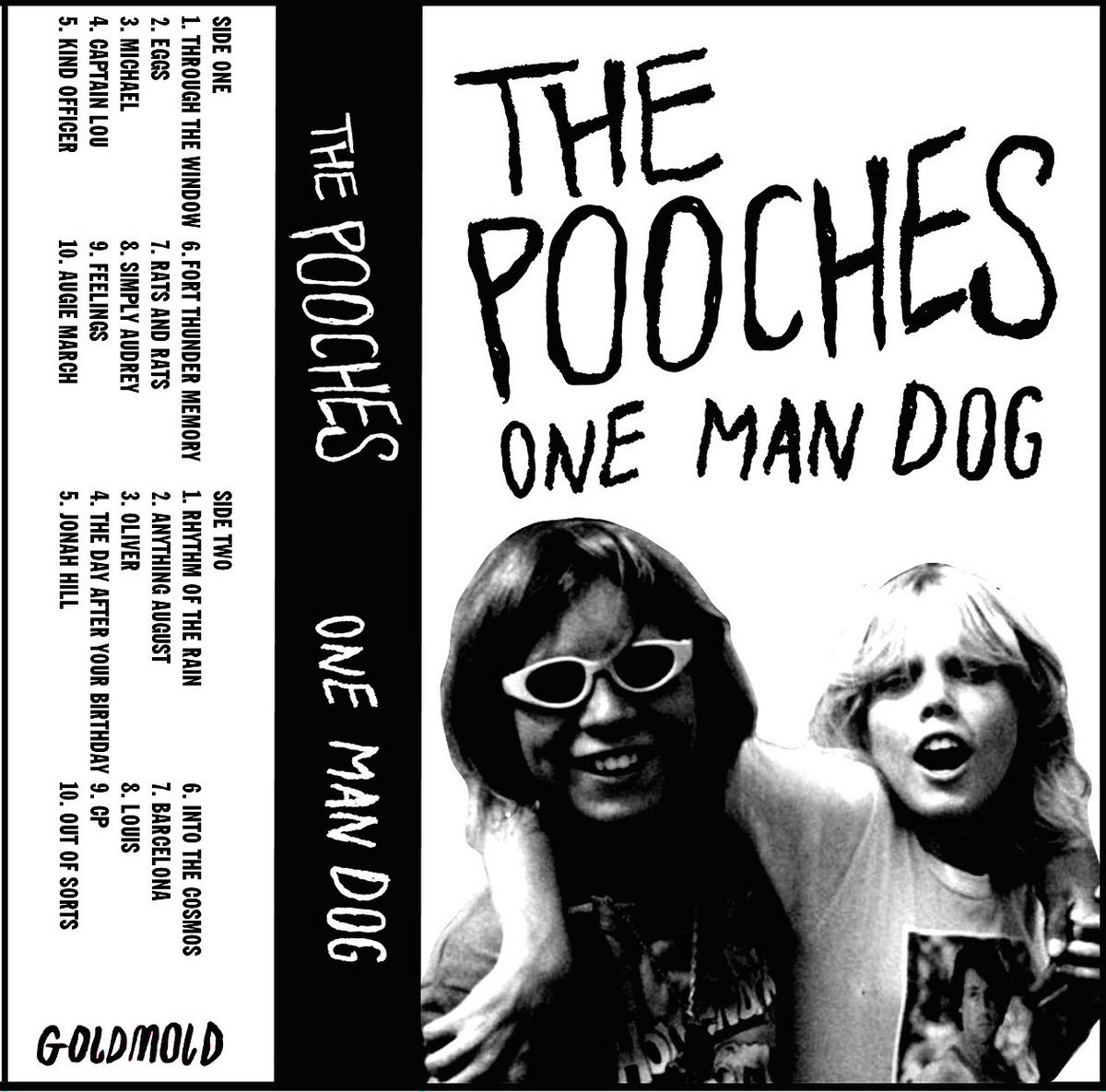

And as recent as 2015, indie rock band, The Pooches, had a song titled, “Fort Thunder Memory” on their album, “One Man Dog.”

The global capitalist society we live under has transformed our mode of production and concept of identity into bland consumption. The space, not the band playing or the art being shown, is unfortunately more important to the casual person than the art at hand. Hence the elite know this and contemplate a future “experience economy” or “rent economy” where we will truly never own or control the means of production but rely on the universal basic income or property of the managerial class who rules over us. Thus we become them or exist on someone else’s fortune.

James Turrell understands and believes that the space is more important than the art. Art requires a higher level of intellectual understanding and demands serious and sincere criticism. The space, however, can be enjoyed by anyone, as the act of tourism is simply walking around in different countries and experiencing a new world. Art may let us experience something of beauty, until space engulfs its limits. Fort Thunder is not in the tradition of making good art, but superseding it into space, and how it influences us as people. We could engineer space, like in design. The Image of the City by Kevin A. Lynch imagines space as an artistic and expressive construction of design through personal mental imagery and experience.

Mat Brinkman and Brian Chippendale understood that Fort Thunder could be engineered as an ideological and expressive statement. The next time you enter someone’s house for a “show” or go to an exotic event like Burning Man, question your surroundings and the environment that influences the acts and their art. The artists in question are not invited to play there but create a sound and image related to the space they are from.

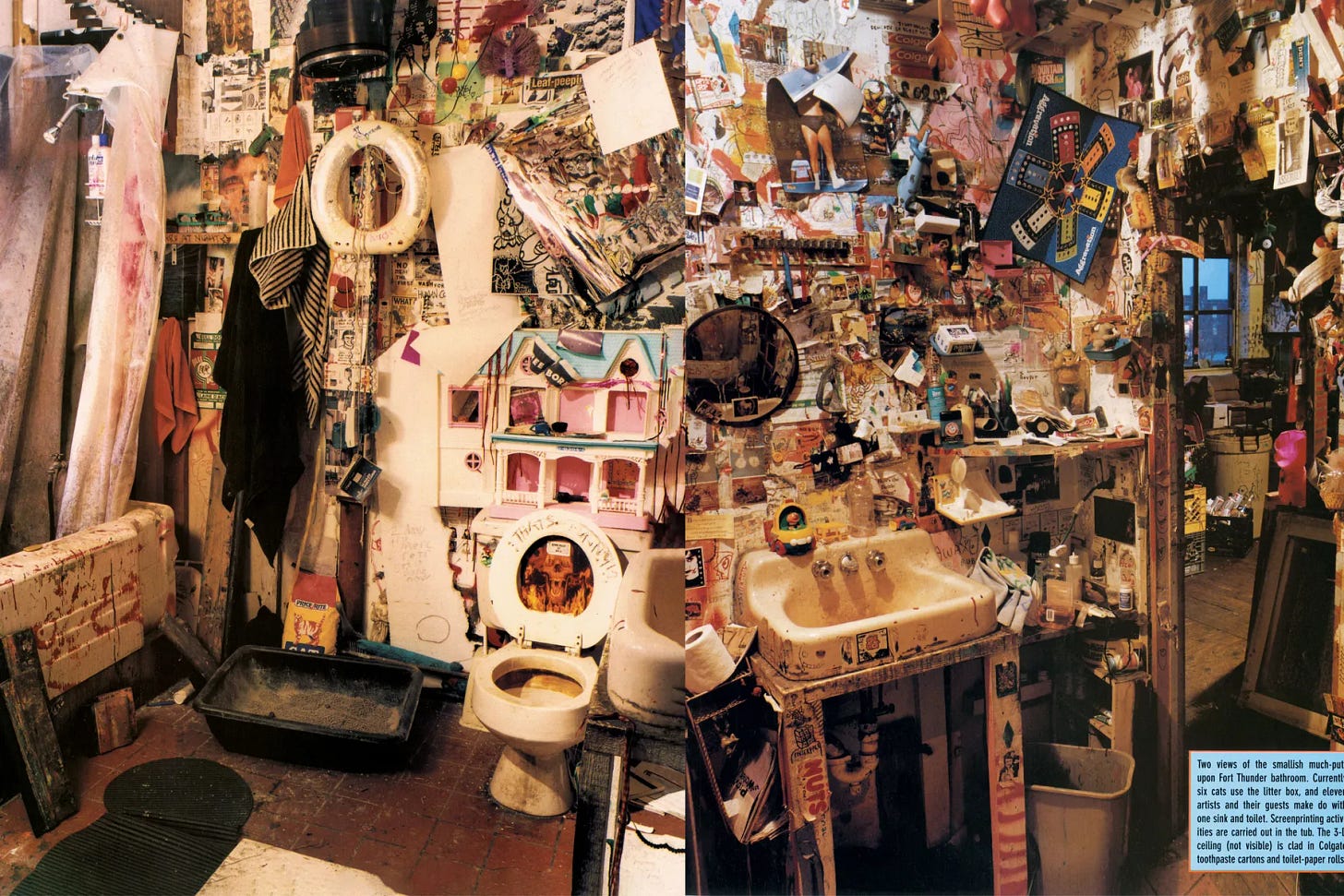

Just take a look at the many images of Fort Thunder and how it influenced the artists there:

The venue, or space, becomes the ideology and purpose of artistic expression, not the "show" or individual playing.

-pe

6-27-2023

Jerzyk. Matthew, “Gentrification’s Third Way: An Analysis of Housing Policy & Gentrification in Providence”, Harvard Law & Policy Review, May 20th, 2013, (https://web.archive.org/web/20220207002910/https://harvardlpr.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2013/05/3.2_9_Jerzyk.pdf)

Schneider, Jeff, “Psychiatric Tissues: The History of the Iconic Noise Rock Band, Arab on Radar”, Pig Roast Publishing LLC., 2018, pg. 147, 148-149.

Ibid., pg. 232.

Ibid., pg. 234.

Spurgeon, Tom, “Fort Thunder Forever,” The Comics Reporter, December 31, 2003, https://www.comicsreporter.com/index.php/briefings/commentary/1863/