The Mysteries of Wunderland: The Art of Andy Looney

About the "Wunderland Toast Society" and its design principles

Andy Looney (1963-) can be described as a clash between Antero Alli and Sol LeWitt, where both got into the same design industry with Dieter Rams as their boss. Looney’s influences trace back to art projects like Cosmic Wimpout in the late 70s, where secret societies would gather around an esoteric dice game influenced by the hippy aesthetics of Peter Max and The Grateful Dead. Ron Hale-Evans has even tried to record this forgotten gamer history and aesthetic on his website, “www.ludism.org.” The subculture around gaming and artistic free will is within the works of Andy Looney, and he represents that silver age advocate of the hippy movement within game design from 1970 up until the late 1990s.

His vintage website Wunderland1 collects information and art detailing back to 1997 when the internet just started. “Wunderland”2 is also the name of his private purple-coated Victorian house in Maryland, where he has “weekly secret meetings of the WTS.” The “WTS” stands for the “Wunderland Toast Society,”3 which echos back to “The Boston Logical Society,” or “W. W. Swilling” who created Cosmic Wimpout originally as a game for a secret communal society. The real mystery behind the art of Andy Looney is the collective community in the DC suburb that has also contributes to his unique and modular game designs. As Looney describes the purple house he lives in, “It’s a fixture in the neighborhood—the great big house where some old hippies live—and yes, we still live there and still do much of the company’s business there.”4

Those names range from Andy’s brother and wife, John Cooper (his close collaborator), and an inner circle of close friends. The Wunderland Toast Society is also kind enough to provide a “Milk Carton” page for “people we use to know.” These connections are important because we understand what exactly is a “collective” and how projects like Wunderland create niche art movements (similar to Boards of Canada’s Music70 project or Fort Thunder). And that’s what the website has accomplished in recorded history.

The best way to view the website is through it’s practical “guide” page and clicking on links from there, or through each year through the “Whats New” page from 1997 all the way to 2012! Wunderland is a treasure trove of vintage internet art from a private collective, and it’s hard to address every aspect of what Looney and his friends have accomplished.

Some funny and absurd vintage web pages include “The Long Hair Index,” “a virtual tour of Ellen’s house,” “The Fictional Andy Looney,” “The Space Under The Window,” “Kristin’s Coasters,” “Living with a Broccoli,” “Iceland the comic,” “Cube Stuff,” “I Love Women,” “Cooking with the Emperor,” “Regarding our Atomic Bomb,” “The Y2K shirt,” “Nanofiction,” “Sketchbook Harvest,” “Stoners in The Haze,” and “What is Smoking Pot Really Like?”

Looney is a characther of many personas. He’s a comic artist, an activist for marijianna legalization, and a self-declared galatic “emperor.”

According to the page “Empire Publications,” Looney in 1986 wrote a manifesto for his art publication.5 It reads,

Empire Publications is a cooperative group of writers and poets, who publish their work independently. They are more interested in getting their work into circulation than in making money. Rather than submitting and resubmitting manuscripts to magazines, the writers of Empire Publications put their efforts into their own books. Each writer sells his books at cost, after doing all of the writing, typing, editing, photocopying, collating, and binding himself. If he can't sell them, he gives them away.

The board of directors of Empire Publications hopes that you enjoy this book, and urges you to buy and read the company's other books.

Your donation furthers the cause of Art.

This ethos is core to understanding Wunderland. The internet gives us technology that wasn’t there in the 1980s. We all become self-published authors marketing ourselves without a label telling us what to do. This incredible freedom of independence liberates the artist to create works that are more true to himself.

One such novel to come from Looney’s mission was The Empty City (which can be read on Wunderland). It describes a world where everyone was playing a game with little pyramids. Along with his friend John Cooper, both of them started creating hypothetical games around these pyramids.

Looney later constructed a video game with these pyramids called “Icebreaker,” and the game was released for the Panasonic 3DO. From the article, “My Obsessions with Pyramids,” Looney had even created a U.S. patent for the design as "Method of Manipulating and Interpreting Playing Pieces."6 While the video game was only about the theme of his pyramids, the purpose of manipulating and interpreting these pieces are Looney’s artistic achievement.

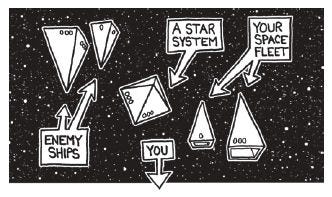

This would lead into the creation of the design for the actual board game using plastic pyramids, “Homeworlds.” Described as “space chess,” Homeworlds is an abstract 2 to 6 player game using two pyramids to construct a personal “star system,” and then building pyramids from there to construct new “stars” and to destroy the opponent. Four or more colored pyramids in the same system can destroy all of them or everything in that star system. This is done by deliberate placing pyramids, or “ships,” into that system to sabotage. Green pyramids build, yellow pyramids move, red pyramids control, and blue pyramids “trade” a different color. Players keep taking single turns until there is a determined winner.

The game notation for Homeworlds is both logical and amusingly artistic. It is possible to write the notation the same way Chess would be played. Game records go back to 2003, and retelling the game reads like a science-fiction story. Homeworlds hypothetically could be played through writing in the email that actually playing with any components in front of anyone. The game becomes a textual experience, like coding in C. Thus Homeworlds is also a dialogue that can be spoken like in philosophical debate.

The design principle of Looney is straight forward with his belief in manipulation and interpretation. Looney said this to University of Maryland in 2023,

“I haven't programmed computers in decades, but I’m still a programmer… What I program now are human beings, the human computers I program to play these games. There are many similarities between a piece of software and the game rules I prepare for players. Writing the actual rules, that’s the most like coding, but designing game rules certainly includes a lot of programming.”7

The freewill and eccentric nature of Looney’s games rely on humanity interactivity and not with computers. “Interactivity” can only exist between two or more human beings, and it’s not something between a human and a touchscreen. Looney’s most famous game Fluxx is a card game with ever changing rules as players adopt to the enviorment of the cards played. While “coding” is an act of writing the rules, “programming” to Looney is introducing new designs, concepts, and mechanics within the game. The “pseudo code” for Fluxx mocks that of C programming, if a machine were to ever create a video game version out of it. Rather, the pseudo code could be read as Looney’s first draft of coding and programming a new board game in his mind before it turns into a reality. There is no software dictating everyday life, and that is the true spirit and passion of board game design that Looney subscribes to.

This reoccuring gag of psuedo code could be understood through Homeworld notation and that true game design can only exist in the mind without a machine.

One of the first games ever constructed with Looney’s pyramids was “Icehouse.” The game does not have any turns. It’s a real-life attempt to create a concurrent “video game” in reality played by humans, as similar to any existing physical sports. The rules for the game were also revised in 2023. As Looney has explained the purpose of Fluxx, “Fluxx is a game about change, and it changes as you play it… We call it the card game of ever-changing rules, and that’s exactly what happens. How you win can change from one turn to the next.”8 A machine cannot understand human flexibility and emotion. It is up to human players to dismantle the code and find avenues of expression outside the machine’s limits.

Looney has created a series of over 100 games worth playing other than Homeworlds or Fluxx. These include Zendo, Aquarius, Are You A Robot?, Chrononauts, Get the MacGuffin, Loonacy, Nanofictionary, Time Breaker, World War 5, and so on.

His own sketches also breathes life into the playful designs he is after. If Friedensreich Hundertwasser decided to draw like Napolean Dyanamite, you would get the cartoons of Andy Looney.

Board game design plays a huge role in the art of Looney and the Wunderland collective. Be it from Cosmic Wimpout, Cosmic Encounter, Nuclear War, Diplomacy, Wiz-War, Illuminati, Junta, Snit’s Revenge, Mertzwig’s Maze, I’m The Boss, 4th Dimension, and even Frog Juice, the list of innovative design principles goes on!

The vintage web aesethics of 16 years worth of artistic material is amazing. Clicking on any year and on any update, we get a Trader Joe’s Fearless Flyer around the Wunderland activities.

…This is only scratching the surface what the Wunderland archive and Andy Looney has to offer for the curious artist. It’s good that all of this has been archived. Even "Weird Al" Yankovic somehow stumbled across Looney’s atomic bomb project!

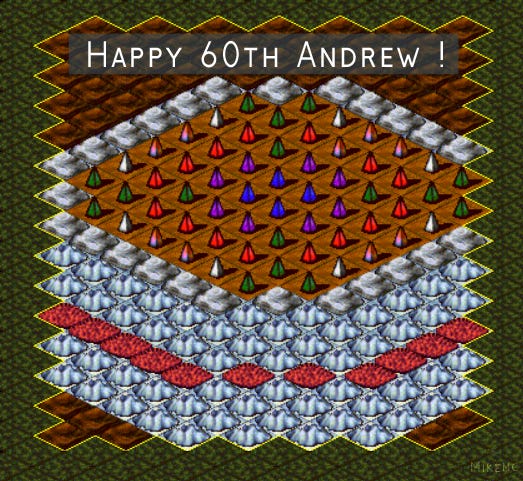

Looney also just turned 60 years old on November 6, 2023. In his blog post, “Now I Am Sixty,” a fan made a new map in the Icebreaker video game in the shape of a birthday cake. This does to show that Looney’s games have a cult following thirty years later.

Check out Looney’s website for yourself. This is the kind of art I aspire to make and to archive as an entire internet project. Andy Looney is one of my favorite artists of all time, and the endless material preserved by Wunderland shows why.

You can also listen to a podcast I did with Andy Looney in 2017, here at this link.

-pe

3-13-2024

http://www.wunderland.com/Home/Guide.html

http://www.wunderland.com/Home/AboutUs.html

http://www.wunderland.com/WTS/WTS.html

https://cmns.umd.edu/news-events/news/kristin-andy-looney-labs-games

http://www.wunderland.com/LooneyLabs/History/EmpirePublications.html

http://www.wunderland.com/WTS/Andy/Icebreaker/pyramids.html

Ibid., [4]

Ibid., [4]