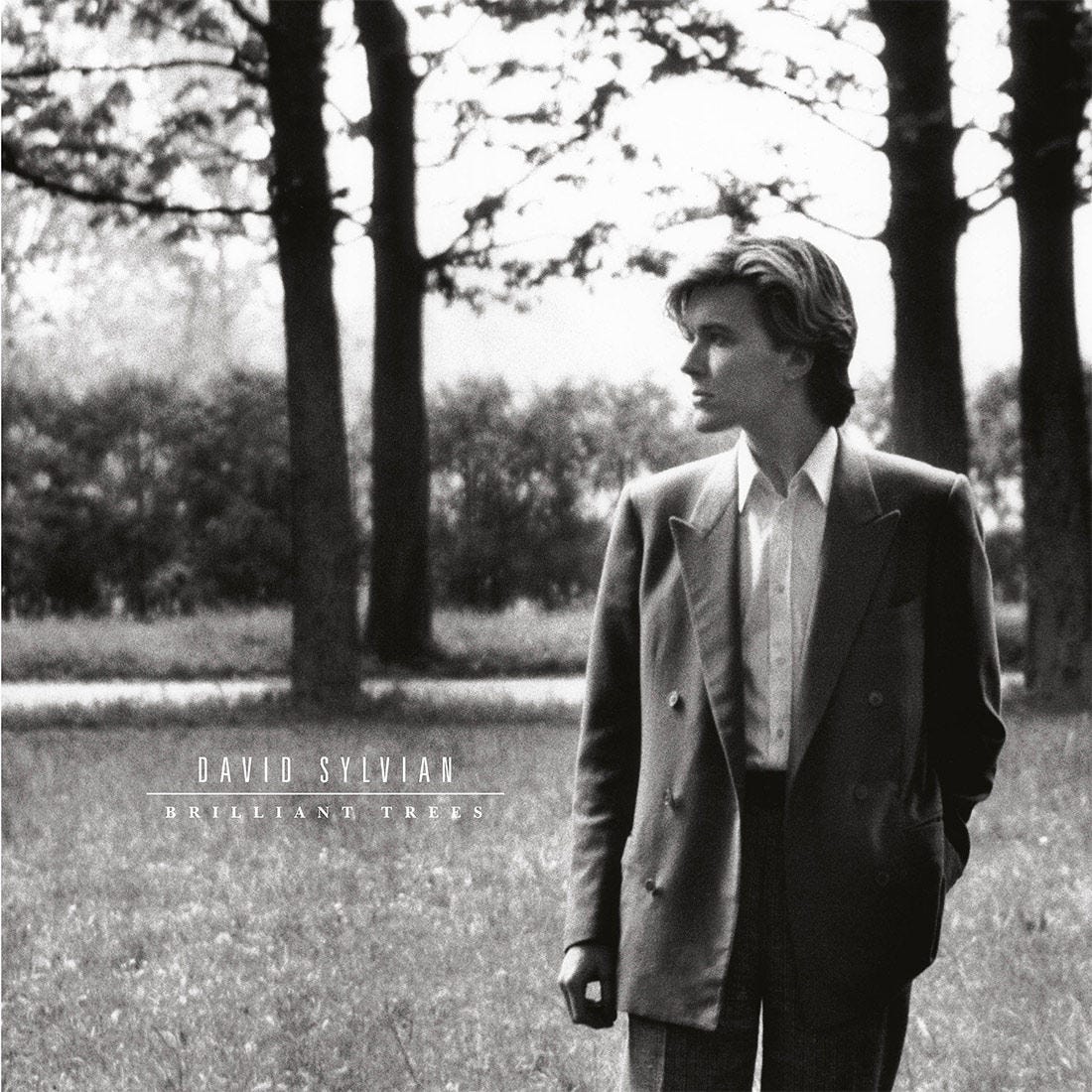

David Sylvian - Brilliant Trees (1984)

A memoir on one of the greatest albums ever recorded

David Sylvian’s first solo album, Brilliant Trees, is one of the greatest albums ever recorded. Yes, it’s up there with the work of Mark Hollis and Talk Talk. And yet, hardly anyone in America knows Sylvian, or his band, by default, called “Japan.”

John Robinson of The Guardian once noted that “Japan's David Sylvian and Talk Talk's Mark Hollis made triumphant, completely unmarketable records (Brilliant Trees; Spirit Of Eden) at the peak of their commercial success.”1 These "unmarketable records” in question, are great works of art against our capitalist system, and the culture of desire that demands so much from smoke and mirrors. Sylvian, who once once a teen icon, expresses himself to the fullest in his first album, and left a trend in both intimate and experimental spaces for future musicians to come.

Controversial as this sounds, Japan’s aesthetics and art direction were based on East-Asian orientalism, creating a hodgepodge of Asian-theme symbols and cultural cues. The band was a predecessor to the electronic sounds of Depeche Mode and the fashion of Duran Duran. Sylvian dressed himself up as an ambiguous, androgynous, Asiatic sex idol, whom the trans people of today would have fallen for him. Japan pushed the boundaries with the 1978 album, Adolescent Sex, which continued with Obscure Alternatives, and 1979’s Quiet Life, enforcing the then of mysticism and wonder of Japanese society, and finally endorsing the hipster lifestyle in 1980’s Gentlemen Take Polaroids and 1981’s Chinese-influenced, Tin Drum.

When Japan broke up in 1982, Sylvian could finally focus on his original work without limits. To the disappointment of his fans (who were all women), Sylvian constructed a personal album against the interest of the record company and created a work of art that was very personal and avant-garde. The album, Brilliant Trees, peaked at #4 on the UK album charts and sold over 100,000 copies.2 This was in part because of the image of Sylvian, portrayed as a handsome and sensitive man, where his celebrity status as a sex icon excused his complicated and demanding work.

It is quite ironic that likely in 2023, Sylvian would be considered “problematic” in the eyes of Asian Americans who are obedient to the white liberal superstructure, and demand that there is something wrong with a white man “fetishizing” Asian culture and openly admitting his love for it (and of course, his desire to get with the women). Sylvian sang about such culture-clashing concerns in his Japan song, “Life in Tokyo,” where he sings, “Oh ho ho, Life can be cruel, Life in Tokyo!” Against all odds, Japan became the first artistic statement of this “Japanophile” movement of the late 70s at a time when the West started opening up to Eastern idealisms, which continues to this day with the liberal and compatible interests of William Gibson and the 2010s K-pop takeover in the global economy.

Brilliant Trees’ front cover photograph was taken by Yuka Fujii, who soon became Sylvian’s girlfriend. This is, in part, a statement of white men getting their way, by seducing the Japanese woman they desire and thus creating a “Eurasian” style of music without any consequences of political incorrectness. A true “Asiansexuality” is expressed within the text of Brilliant Trees.

Sylvian hired the best in the industry, from Holger Czukay of Can to Ryuichi Sakamoto of Yellow Magic Orchestra. He already worked with Sakamoto to create the synthpop track, “Forbidden Colours,” based on Yukio Mishima’s novel of the same name. Sylvian was dedicated to combining his interest in literature with that of sound, and both the Western and Eastern influences would help shape an album that was ahead of its time. If existential “freedom” is what the American West desires, it is tradition and spirituality from the East that confines them to a hybrid version of “the good life.” Sylvian bounces these two values respectfully, where he can become a part of the Asian identity movement while steering towards the liberal “freedom” that he contemplates as an eccentric artist for the West.

Many experimentations were used to craft this album. Anywhere from synths, traditional bass, French horn, and the dictaphone were used as instruments. In just under 40 minutes and 7 tracks, Brillant Trees delivers a repressed emotion of desire and want towards a generational audience that can’t speak for itself. The album is even handwritten by Sylvian himself, in it’s track titles and production notes.

Sylvian’s brother, Steven Jansen, contributes to the album as well, adding a touch of the same darkness and quietness his brother is known for. Jansen later worked with Anja Garbarek on his 2007 album, Slope. Garbarek is also a fan of the sparse and minimal sound of the “third stream” jazz music. Her 2001 tracks, “The Gown” and “Big Mouth” feature the work of Mark Hollis, thus continuing the tradition of inward and introverted acoustic music found on Brilliant Trees. It is no surprise that the Sylvian family is quite aware of the avant-garde connections in popular music.

The opening single, “Pulling Punches,” is the radio-friendly highlight of the entire album. It’s ruled by a continuous bass slap melody, followed by shrieking guitars, and David’s unorthodox and ever-changing singing without ever repeating itself. The guitar solo almost feels like it belongs on a noise record, and not on a poppy art-rock emulation of Fine Young Cannibals or Bow Wow Wow. The album cut leads into a church-like chorus at 3:17, where the listener falls out of concentration. This chorus variant was omitted from the single version.

The music video for Pulling Punches does reek of the 1980s cliches of watercolors and glam. The 2011 act, Gotye, copied the aesthetics and visuals of the Pulling Punches videos, and created their own mock nostalgic throwback song, “Somebody I Use To Know.”

The second track, “The Ink In The Well,” is another classic. The video was directed by Anton Corbijn of Depeche Mode and U2 fame. Sylvian was on a path to becoming the next David Bowie, and help from Corbijn could only solidify this legacy.

It is also interesting that David Bowie was a fan of Asian culture, and he once dated Sandi A. Hohn, known as Sandii in the synthpop group, Sandii & the Sunsetz. There are multiple accounts and experiences that Bowie showed his Asiansexuality early on, but later concealed it when it became too obvious in the press. Sylvian never backed down and kept with the Asian aesthetics even during his spotlight.

The Ink In The Well continues the theme of nostalgia, with his interest in Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau. It is an intimate song that fuses jazz and guitar work, and the chorus is somehow catchy in the most sophisticated way possible. “The rope is cut, the rabbit is loose, Fire at will in this open season, The blood of a poet, the ink in the well,

It's all written down in this age of reason.” Sylvian later dabbled into both photography and written poetry, and this song shows an early snapshot of his creative potential. The ending chanting and horn solo is genius.

Furthermore, the next track “Nostalgia” is just about. What could have been a single, ended up being something that could might as well be played in irony on the Netflix show, Stranger Things. Sylvian was interested in chanting to a point, that the track itself becomes holy. The reverb, delay, and skimpy percussion turn into one of the greatest songs ever written. The response melody of the guitar lick is a companion to the intellect lyrics of the chorus. The probability of synth noises, exotic instruments, and singing creates an environment that feels like something Cyndi Lauper could have written in a different timeline. Yet, Sylvian is never dedicated to pop structure and rather wants to focus on improv.

Side A of the album ends with the lead single, “Red Guitar.” I’ve heard Red Guitar multiple times on NHK World News or NHK English programs. I swear I might have come across a Peter Barakan program where Red Guitar was being played as the film showcased “the wonderful and amazing world of Japanese culture.” No doubt in my mind, Peter Barakan and David Sylvian were connected at one point in time. There’s even an old interview Barakan did with Sylvian that was recorded for Japanese TV.

And yes, the music video for Red Guitar was also directed by Anton Corbijn.

Red Guitar feels like Björk’s “Venus as a Boy” without the electronics. Red Guitar might have been in the 1994 French film, Léon: The Professional, and fans would have never noticed.

Red Guitar is also personal and passionate as it could be as friendly and mindless elevator muzak to some Japanese shopping mall out in Sapporo. Sylvian was pushing the third stream interset of classical and jazz influence that was gaining ground in the 1980s. Electronic music felt too polished and fake, while a return to jazz felt that music became more lively and real. You could have experimental and sound design, but it didn’t have to be constructed on a synthesizer.

Side B begins with “Weathered Wall.” The slowness and drone of synths and drums start to appear. Sylvian hums in a vocoder to create the monotone sound of mediation. Sometimes, playing a single note, followed by another, is all that is needed to create music. Just like in “Nostalgia,” Weathered Wall feels more like an environment that was created during a time when such experimentation was shunned in 1984. The samples make an additional nice touch, which would become more common in industrial music of the 1990s. The The’s 1989 album Mind Bomb comes close to the abstract environment Sylvian was experimenting with early on. The rage was to play without excuses and to perform something that was done on the first take, in search for an authentic sound. It’s the ethereal and natural sounds of ethnic traditions, also found in the work of Dead Can Dance.

The next track, “Backwaters,” continues with synth exploration and improv looping. For a bit, it feels like Backwaters is a continuation of Weathered Wall, and jamming for the sake of it.

The final track, “Brilliant Trees,” continues the humming in Weathered Wall. There is a focus on the space between the synth and the singing of Sylvian. A concern of “heaven” is found in the lyrics, as desire is the main theme of the album. “And there you stand, Making my life possible. Raise my hands up to heaven, But only you could know… My whole life stretches in front of me, Reaching up like a flower, Leading my life back to the soil.” At 4:40, the song transforms itself itself another tribal jam session, before the album closes. It sounds so close to the cyber gamelan music of the 1988 anime movie, Akira, or what Yukihiro Takahashi was doing at the time.

Side B feels like a different composition than the pop selection on Side A. Together, they make up an album that is daring, and willing to criticize the market fad that “solo albums are just inferior experimental works for bigger brand albums to come.” Instead, the album is actually Sylvian’s magnum opus, detailing the fine interest in attachment, love, and total expression of the self against a society that hates the alien. It's better than Japan!

Sylvian produced an album that listeners were not ready for. He would continue creating avant-garde work until he escaped from pop music entirely. In 2018, Sylvian expressed his frustration with the art world,

“I'm not currently thinking about a future in the arts. To quote Sarah Kendzior from her book The View From Flyover Country, “In an article for Slate, Jessica Olien debunks the myth that originality and inventiveness are valued in U.S. society: 'This is the thing about creativity that is rarely acknowledged: Most people don't actually like it.”3

Currently, Sylvian lives in south New Hampshire, in a barn he converted into his studio. The Guardian in 2005 suggested he was “turning Japanese.”4 Sylvian lives the life of the hermit, and will produce art when the time strikes. He doesn’t care about being famous or playing in arenas with sellout numbers. The world isn’t ready for him, or his art. He keeps close ties with his Japanese associates and keeps pushing the boundaries of experimental music.

Sylvian is like a Mineo Maya character, something out of Patalliro!. I’m not sure what to make of him. Either he’s living his best life as an Asian-influenced cosmopolitan bohemian, or he’s just like everyone else and got lucky with his music. He’s tired of that boring music on the radio, and he wants to show his fans that he’s more than some teen idol. Brilliant Trees is one of the best albums of the 1980s, if not, of all time, because of it’s dedication to creating something new, and to project a subculture that is Asian-friendly, and artsy, in it’s design. More listeners could have gone the path of Sylvian and created a work of innovation that not only touches the soul but is romantic in all of its splendor and wordplay.

It’s true. All the cool stuff was going down in Tokyo. Sylvian assimilated to that Japanese standard and beyond what John Lennon or Yoko Ono could have done. Sylvian is the pioneer of the Western Japanophile movement and their love for everything Asian. He executed a personal record about the sensitive artist and his condition. This, I believe, is true Platonism. It motivates the sensitive white man to create art about himself, and the things he loves, beyond any limits that stop him.

I assure you this 39-minute album is the greatest record of all time.

-pe

9-22-2023

Robinson, John, “Pieces of eighties,” The Guardian, April 23, 2004, (https://www.theguardian.com/music/2004/apr/24/popandrock1).

https://www.bpi.co.uk/award/1093-2575-2

Bonner, Michael (13 July 2018). "An interview with David Sylvian". Uncut. Archived from the original on August 9th, 2020. (https://www.uncut.co.uk/features/interview-david-sylvian-106403/).

Cowley, Jason, “Turning Japanese,” The Guardian, April 5, 2005, (https://www.theguardian.com/music/2005/apr/10/popandrock1)

It was weird coming across this article-- I never meet anyone else who's into David Sylvian! Definitely enjoyed reading that.